Have you ever wondered why some foods taste bitter but are not harmful?

While a bitter taste is often considered a warning sign of potentially toxic substances, not all bitter-tasting things are dangerous.

For example, some nutritious peptides and amino acids taste bitter even though they are safe and important for our health.

A new study by the Leibniz Institute for Food Systems Biology at the Technical University of Munich has uncovered why this happens.

The research, published in the journal Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, offers the first explanation for this puzzling phenomenon.

Our sense of taste helps us choose what to eat. Sweet and umami tastes tell us a food is rich in energy and nutrients.

Salty tastes help us maintain our body’s electrolyte balance.

Sour tastes can warn us of unripe or spoiled food, and bitter tastes often signal potentially toxic substances.

This makes sense because many toxic plants, like nux vomica or manioc, have bitter compounds.

However, not everything bitter is harmful. For instance, some protein fragments, known as peptides, and free amino acids can taste very bitter but are actually nutritious.

An interdisciplinary research team led by molecular biologist Maik Behrens investigated this seemingly contradictory situation.

Using a special cellular test system, the Leibniz team found that five of the approximately 25 human bitter taste receptors react to both amino acids and peptides as well as bile acids.

Amino acids and peptides are produced when proteins break down and are abundant in foods like cream cheese and protein shakes. Bile acids, on the other hand, are not food components but play essential roles in our body.

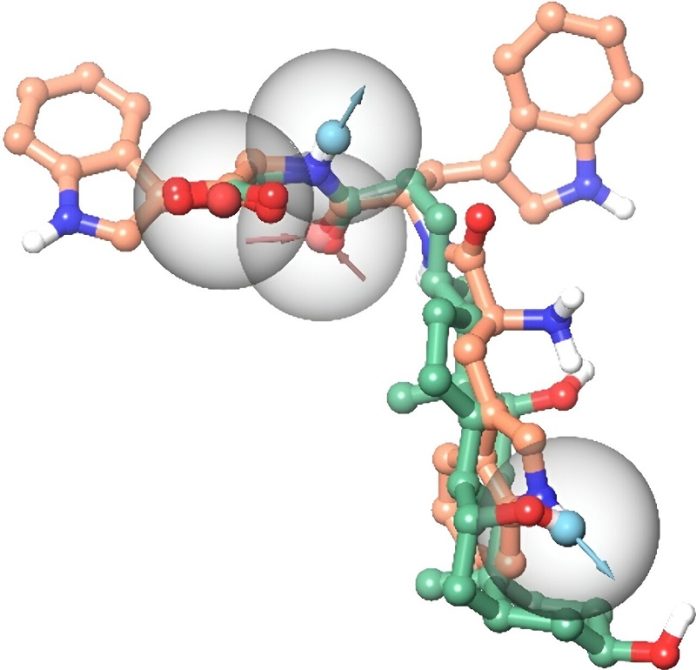

The researchers discovered that these bitter-tasting peptides can take on a 3D shape similar to bile acids when they bind to the taste receptors. This similarity might explain why the same bitter taste receptors react to both groups of substances.

Bioinformatician Antonella Di Pizio explains, “Our modeling experiments show that a certain bitter-tasting peptide can adopt a functionally active 3D shape similar to that of bile acids inside the receptor binding pocket. This coincidental similarity could explain why the same set of bitter taste receptors react to both groups of substances.”

First author Silvia Schäfer adds, “Our genetic analyses show that the ability to recognize both bile acids and peptides is highly conserved in three of the bitter taste receptor types and can be traced back to amphibians. This indicates that recognizing one of these groups is important across species.”

“Bitter taste receptors and bile acids existed millions of years before the typical bitter substances of today’s plants and long before humans—in fish, for example.

This supports the idea that bitter taste receptors originally also regulated important physiological processes, not just warned against toxic substances,” says Behrens.

The findings suggest that bitter receptors have additional roles in human health beyond helping us select food. These insights into the complex systems of taste perception could lead to new discoveries about how our bodies work and how to improve our health.

If you care about nutrition, please read studies that vitamin D can help reduce inflammation, and vitamin K may lower your heart disease risk by a third.

For more information about nutrition, please see recent studies about foods that could sharp your brain, and results showing cooking food in this way may raise your risk of blindness.