In recent years, batteries have become essential in our daily lives, powering everything from smartphones to electric cars.

However, most batteries today have some problems.

They often use liquid electrolytes and carbon-based anodes, which can be unsafe, have a short lifespan, and don’t perform well at high temperatures.

There’s a growing need for batteries that work well in extreme conditions, such as the high temperatures needed in industries like medical device sterilization, underground exploration, and thermal reactors.

This demand has led researchers to look for solid electrolytes that are safer and work better with lithium metal anodes, which can store a lot of power.

A research team led by Professor Dong-Myeong Shin from the University of Hong Kong (HKU) has made a significant breakthrough.

They developed a new type of lithium metal battery that promises to be safer and last longer, even at high temperatures.

Their innovation is based on creating a special kind of polymer electrolyte that doesn’t crack. This is crucial for the battery’s long life and safety.

The team’s findings were published in the journal Advanced Science.

The title of the paper is “Accelerated Selective Li+ Transports Assisted by Microcrack-Free Anionic Network Polymer Membranes for Long Cyclable Lithium Metal Batteries.”

The new polymer electrolytes are made using a simple one-step process.

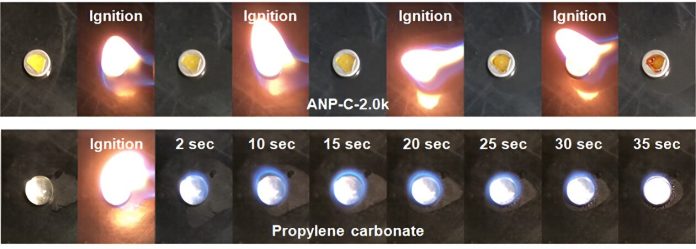

They have several important features, including resistance to dangerous dendrite growth, being non-flammable, and having high electrochemical stability. They also have an ionic conductivity of 3.1 × 10−5 S cm−1 at high temperatures.

These improvements are due to borate anions in the polymer membranes. These anions help transport lithium ions faster and prevent dendrite formation. As a result, the new lithium metal batteries can safely store energy and last a long time at high temperatures.

They can keep 92.7% of their capacity and have an average efficiency of 99.867% over 450 cycles at 100°C. In comparison, traditional liquid electrolyte lithium metal batteries usually last fewer than 10 cycles at these temperatures.

This breakthrough could lead to further advancements in designing anionic polymer electrolytes for next-generation lithium batteries. Dr. Jingyi Gao, the first author of the paper, said, “We believe this innovation opens doors for new battery chemistries that can revolutionize rechargeable batteries for high-temperature applications, emphasizing safety and longevity.”

Professor Shin added that besides high-temperature uses, these new electrolytes could also enable fast charging due to their low overpotential. This means electric vehicles could recharge as quickly as drinking a cup of coffee, marking a significant step towards a clean energy future.

This new development in battery technology not only enhances safety and longevity but also opens up new possibilities for fast-charging applications, making it a promising solution for future energy storage needs.