Researchers at the University of Copenhagen have created a new type of biodegradable plastic made from barley starch and sugarbeet waste.

This eco-friendly material, which turns into compost when it ends up in nature, could help reduce plastic pollution and lower the environmental impact of plastic production.

Plastic pollution is a massive problem, with large islands of plastic floating in our oceans and microscopic particles found in our bodies.

Plastics are durable, flexible, and cheap, making them widely used in everything from packaging to clothing and airplane parts. However, they are also tough to recycle and their production emits more CO2 than all air traffic combined.

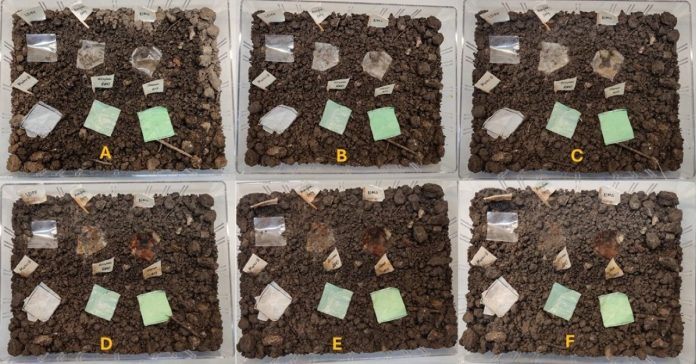

Now, scientists at the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences have developed a new type of bioplastic that decomposes completely in nature within just two months.

This material, made from natural plant materials, could be used for many applications, including food packaging.

“We have a huge problem with plastic waste that recycling alone can’t solve,” says Professor Andreas Blennow. “That’s why we’ve developed a new bioplastic that is stronger and more water-resistant than current bioplastics. Our material is 100% biodegradable and can turn into compost if it ends up in the environment.”

Globally, only about 9% of plastic is recycled. The rest is either incinerated, ends up in nature, or is dumped in large landfills. While bioplastics already exist, they are often misleadingly named. Many of them don’t break down easily in nature and require special industrial composting facilities. Even then, only a small part can be recycled, with the rest ending up as waste.

The new material created by Blennow’s team is a biocomposite made from amylose and cellulose, which are common in many plants. Amylose is extracted from crops like corn, potatoes, wheat, and barley. The researchers developed a barley variety that produces pure amylose, which is less likely to turn into paste when in contact with water.

Cellulose, a carbohydrate found in all plants, is used to make cotton and linen fibers, as well as wood and paper products. The cellulose used by the researchers is nanocellulose made from sugar industry waste. These tiny fibers give the material its strength.

By combining amylose and cellulose, the researchers created a strong and flexible material that could be used for shopping bags and packaging. The bioplastic is made by dissolving the raw materials in water or heating them under pressure to create small pellets that can be shaped into various forms.

Although the researchers have only made prototypes in the lab so far, Blennow believes that large-scale production could start soon. The production chain for amylose-rich starch already exists, with millions of tons produced each year for the food industry.

The researchers are now working on a patent application and collaborating with Danish packaging companies to develop prototypes for food packaging and other uses, such as car interior trims. Blennow predicts that the new material could become a reality within one to five years.

“It’s quite close to the point where we can start producing prototypes,” says Blennow. “I think it’s realistic that we will see different prototypes for packaging, such as trays, bottles, and bags, developed within one to five years.”