In a fascinating development, a recent study published in the journal Diversity has shed new light on how whales and dolphins, some of the ocean’s most intriguing creatures, developed the ability to use echolocation.

This research, co-authored by Jonathan Geisler, Ph.D., and Robert Boessenecker, Ph.D., dives into the ancient history of these marine mammals to understand their remarkable sonar capabilities.

Whales and dolphins, lacking external ears, have mastered echolocation, a technique that involves emitting high-pitched sounds that bounce off objects and return to them, allowing these animals to “see” their surroundings through sound.

This ability is particularly vital for navigating and hunting in the dark depths of the oceans.

The study uncovers that the peculiar asymmetry in the skulls and tissues near the blowhole of these creatures plays a crucial role in their echolocation abilities.

This asymmetry – where one side is larger or shaped differently than the other – helps in producing the sounds necessary for echolocation. Additionally, their lower jawbone, filled with fat, acts like a conductor for sound waves, aiding in directional hearing.

Understanding how whales and dolphins evolved to possess this sophisticated natural sonar has long been a puzzle for scientists.

The recent research offers significant clues by analyzing fossils, including two ancient dolphin species from the genus Xenorophus, one of which is a newly discovered species.

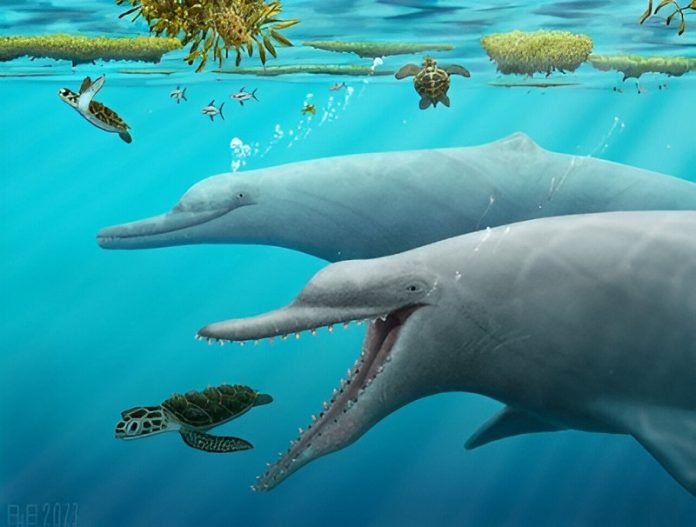

These ancient dolphins swam in Eastern North America’s waters around 25–30 million years ago and were about three meters long. They likely fed on fish, sharks, sea turtles, and small marine mammals.

Xenorophus, despite its external resemblance to modern dolphins, had several molar-like interlocking teeth, similar to ancestral land mammals. Like today’s toothed whales and dolphins, Xenorophus exhibited asymmetry around the blowhole, though not as pronounced.

An intriguing aspect of Xenorophus was the distinct twisting and shifting of its snout to the left, a feature linked to the asymmetrical placement of fat bodies in the jaw that enhances directional hearing.

This snout bend and the tilting of fat bodies in Xenorophus’ lower jaws may have functioned similarly to the asymmetrical ears of owls, aiding in pinpointing the location of prey based on sound.

Although Xenorophus had less pronounced asymmetry near the blowhole and may not have been as skilled at producing or hearing high-pitched sounds as present-day toothed whales and dolphins, it was capable of determining the location of sounds.

This suggests that Xenorophus was a key transitional species in the evolution of echolocation in these marine animals.

Boessenecker notes that while asymmetry is observed in other ancient whales, Xenorophus shows the strongest asymmetry of any known whale, dolphin, or porpoise, living or extinct.

The study indicates that the blowhole-focused asymmetry seen in today’s toothed whales and dolphins can be traced back to Xenorophus and its relatives.

However, the snout twisting and shifting characteristic of Xenorophus is no longer present in modern species, making it a crucial piece in the puzzle of echolocation evolution.

Geisler emphasizes the significance of asymmetry in this evolutionary process. While biological symmetry is a major feature in the evolutionary history of animals and humans, their research highlights the role of asymmetry in adapting to different environments.

This finding encourages a closer examination of asymmetry in fossils, rather than dismissing it as individual variation or geological distortion.

Moving forward, the researchers plan to examine other toothed whales and dolphins, looking for the characteristic snout bent to one side.

These future studies could reveal whether this feature was common among ancient odontocetes and further illuminate the fascinating journey of echolocation evolution in these remarkable marine mammals.