In an innovative stride towards sustainable fuel solutions, researchers at Lund University in Sweden are delving into the realm of liquid hydrogen fuel.

The system they’re investigating could revolutionize how we fuel our cars, resulting in a method that’s comparable to the current way we fill our tanks at gas stations, yet notably, is free from greenhouse gas emissions.

A glimpse into liquid hydrogen fuel

Imagine a scenario where your car runs smoothly along the roads, powered not by conventional fossil fuels but a special kind of liquid.

This liquid, when passed through a solid substance (a catalyst), transforms into hydrogen.

The hydrogen then powers your vehicle, and the only byproduct of this process?

Simple water. This concept isn’t a distant sci-fi dream, but a model being actively explored by scientists aiming to create a more sustainable future.

From Concept to Reality: LOHC

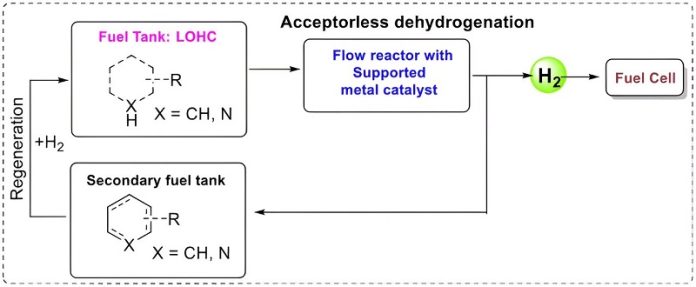

Ola Wendt, a professor at the Department of Chemistry at Lund University, along with his team, has been meticulously exploring this concept known as Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHC).

While the LOHC model itself isn’t entirely new, the challenge lies in finding a catalyst that can efficiently extract hydrogen from the liquid fuel.

The researchers are experimenting with liquids like isopropanol (commonly found in screenwash) and 4-methylpiperidine, running them through a catalyst, and successfully converting more than 99% of the hydrogen gas present.

How Does This System Work?

Here’s a simplified breakdown:

- The liquid fuel, which is “charged” with hydrogen, flows through a catalyst.

- The catalyst extracts hydrogen from the liquid, which can then be used in a fuel cell to produce electricity for the vehicle.

- The remaining “spent” liquid continues into a separate tank.

- The vehicle emits only water, causing no harm to the environment.

When it’s time to refuel, the spent liquid is removed and replaced with freshly charged liquid, somewhat like how we refill our vehicles with petrol or diesel today.

This spent liquid isn’t discarded but is recharged with hydrogen to be used again, establishing a circular, sustainable system.

An intriguing aspect is that this could potentially be applied to larger vehicles like buses and trucks, perhaps even aircraft.

Larger tanks might allow these vehicles to traverse almost equivalent distances as they would with a tank of diesel but with a 50% higher energy conversion compared to compressed hydrogen, as per Wendt.

Although this all sounds incredibly promising, a few hurdles remain. One of them is the lifespan of the catalyst, which is currently quite limited.

Furthermore, the catalyst relies on iridium, a precious metal, which can pose both availability and cost challenges.

However, Wendt notes that the amount needed – roughly two grams per car – is quite reasonable, especially when compared to the three grams of precious metals used in today’s catalytic converters for exhaust cleaning.

Ten Years to a Liquid Hydrogen Future?

While it is rooted in fundamental research, Wendt believes that if societal interest and economic viability are assured, this concept could transition into a tangible product in a decade.

But there’s another elephant in the room: how hydrogen itself is produced. Currently, most hydrogen production isn’t exactly eco-friendly, being mostly derived from natural gas, with carbon dioxide as a byproduct.

The pursuit of “green hydrogen,” produced by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using renewable energy, is vigorous but still in progress.

Wendt underscores that for such innovative and eco-friendly alternatives to truly take root, political decisions are pivotal.

The affordability and accessibility of renewable options need to be enhanced to truly allow them to compete with fossil fuels, and this demands political will and strategic policy-making.

In a nutshell, while we steer towards a future where our vehicles zoom, powered by clean, circular hydrogen fuel systems, the scientific, economic, and political wheels must turn in unison, driving us toward a greener, sustainable tomorrow.

Follow us on Twitter for more articles about this topic.

Source: Lund University.