Scientists from the University of Cambridge and the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies have made a groundbreaking discovery about the distribution of earthquakes in Britain and Ireland.

Their research reveals why Britain experiences more frequent earthquakes compared to its neighbor Ireland, where seismic activity is almost non-existent.

By examining the thickness of the tectonic plates beneath the two regions, the researchers have shed light on this long-standing puzzle.

Using a technique called seismic tomography, similar to a CT scan in medicine, the researchers generated a computer-generated image of Earth’s interior.

This imaging technique allowed them to observe the variations in the thickness of the lithosphere—the solid outer part of Earth—across Britain and Ireland.

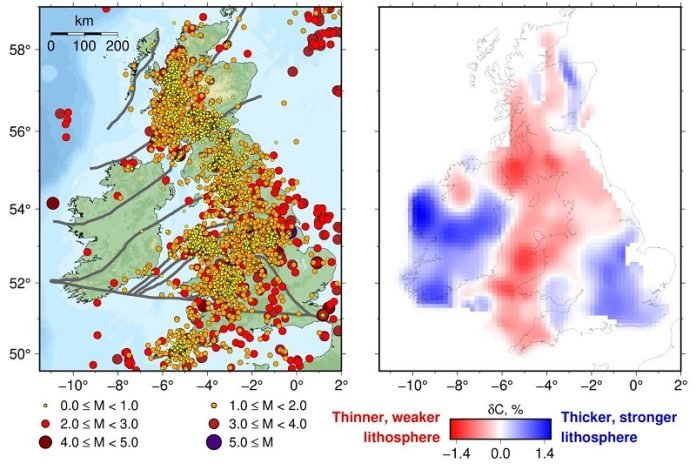

The study found that the lithosphere beneath western Britain is thin and weak, making the rocks in this region more prone to bending and triggering earthquakes.

In contrast, Ireland sits atop a thick and strong lithosphere, which explains the absence of earthquakes.

The difference in plate thickness is the key factor behind the divergent seismic activity between the two regions.

Although the UK is situated far from plate boundaries where most earthquakes occur globally, it experiences around 200 to 300 small to moderately-sized tremors each year.

These earthquakes are mostly concentrated along the western side of mainland Britain, with only a few strong enough to be felt.

While they may not reach the magnitudes observed in other parts of the world, understanding their occurrence is essential for engineering projects to consider seismic hazards.

The contrast in seismic activity between Britain and Ireland was first observed by seismologist Joseph O’Reilly in 1884.

Various theories, such as localized shifts in the land after the melting of ice sheets, have been proposed to explain this phenomenon.

However, a recent study suggests that these theories do not fully account for the observed seismic patterns.

To gain further insights, the researchers deployed a network of seismometers across Ireland, which allowed them to examine the crust below in detail.

The results demonstrated a close correlation between earthquake distribution and the thickness and strength of the underlying tectonic plate.

Ireland’s stronger and thicker lithosphere prevents it from buckling, resulting in fewer earthquakes.

In contrast, Britain’s thin and weak lithosphere allows for crumpling and breaking, leading to tremors along ancient faults near the surface.

The study also explains more localized earthquake patterns within Britain and Ireland. For instance, the occurrence of earthquakes in Co. Donegal, Ireland, can be attributed to a weaker section of the lithosphere in that area.

Similarly, patches of stronger tectonic plate beneath eastern Scotland and south-eastern England result in fewer earthquakes.

This groundbreaking research has finally unraveled the mystery behind the contrasting seismic activity in Britain and Ireland.

The link between lithosphere thickness and earthquake occurrence provides crucial insights into earthquake distribution within tectonic plates. The findings not only have implications for Britain and Ireland but also help understand earthquake patterns in other regions worldwide.

The researchers’ future investigations will focus on Africa and other continents to explore similar connections between lithosphere thickness and seismic activity.