Ira Goodman woke up in the middle of the night drenched with sweat. His head pounded like nothing he’d experienced in all his 31 years. The room spun and he felt extremely nauseous.

He’d eaten an enchilada the night before, so he figured these were symptoms of food poisoning.

He stumbled to the bathroom, vomited and returned to bed. He slept fitfully. By the time morning arrived, he’d staggered to the bathroom several times, once falling into a wall and sending a framed photograph crashing to the floor.

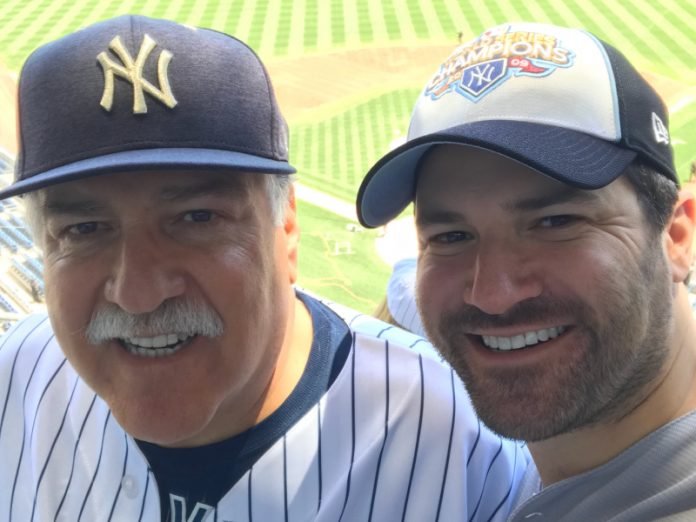

The next day, Ira called his father, Marc Goodman, and described his symptoms, which included feeling dehydrated. Marc stopped by that evening to deliver some Gatorade.

“The way he looked, and with that headache, it seemed a lot worse than food poisoning,” Marc said.

He decided to take his son to the emergency room of the NYU Medical Center. On their way out of the apartment building, Ira was so limp that Marc had to prop him up.

Doctors had no idea what was wrong with Ira until they performed a CT scan and an MRI of his brain and neck.

“Your son had a major stroke,” doctors told Marc.

Doctors concluded that Ira had torn or damaged the inner lining of an artery in his neck, which is called a vertebral artery dissection. It causes a clot to form, which expands until it suppresses blood flow to the brain. They had no idea why it happened to Ira.

The next day, problems mounted. Damage from the stroke was causing fluid to build up in Ira’s brain, causing dangerous pressure.

“They said they had to drain it and that Ira had a 50-50 chance of making it, which is not what you want to hear with your child,” Marc said.

The procedure was successful. In a few days, Ira was transferred from the neurosurgery ICU to the stroke unit.

“Amazingly, I felt normal pretty quickly,” Ira said. “I had headaches and was tired, but that was to be expected. I was definitely the youngest patient – about the same age as many of my doctors.”

He was sent to the rehabilitation wing for five days of balance and occupational therapy, which to him felt unnecessary.

Again, he was the youngest patient around. So many friends visited that he was moved to a different room, so as not to disturb his elderly roommate.

Within a few months, Ira made a full recovery.

“Honestly, I felt even healthier than before,” he said, though he was shaken by the fact he could have died.

Three and a half years later, Ira was 35 and undergoing a routine physical that led to the discovery of a new problem: an ascending aortic aneurysm, an abnormal bulge in the wall of the aorta, the major blood vessel that carries blood from the heart to the body.

Because Ira had no earlier chest MRI to compare it to, a cardiac surgeon advised him to wait six months to check it again.

Ira didn’t like that idea. So he saw an aorta specialist.

“He told me I could be fine forever, but there was no way of knowing,” Ira said. “It could just tear or burst.”

Rather than wait for the worst-case scenario, Ira underwent an operation in which the damaged section of his aorta was replaced with a synthetic graft.

As with the stroke, doctors aren’t sure what caused the aneurysm.

Ira is now 39 and back to being physically active. He plays softball, golf, tennis and goes to the gym.

He’s also active with the American Heart Association’s Young Professionals Committee in New York City, which works to raise awareness and funds for heart and stroke issues and research. He values the friends he’s made through the group.

“Everything I’ve been through is a part of me now, but not everyone can relate to it,” he said. “It’s nice to have friends who can.”

Not only is Ira the chair of the group’s board, he’s been their top fundraiser for the past two years, raising around $15,000 each year through their main event, the Young Professionals Red Ball.

“People ask, ‘What’s your secret?'” he said. “A stroke and an aneurysm by the time I was 35? That combination makes for a strong fundraising story.”

If you care about stroke, please read stories about orthopedic surgeon becomes patient after stroke at 48 and findings of son helps dad after back surgery, then dad helps son after stroke.

For more information about stroke and your health, please see recent studies about testosterone therapy can reduce heart attack and stroke and results showing that scientists can detect cognitive, functional decline 10 years before stroke.