Bombardment of Earth’s surface by asteroids six or more miles long likely delayed the accumulation of oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere.

New evidence shows the number of ancient, large celestial bodies that crashed into Earth was up to 10 times higher than previously believed.

This finding has led a team including a UC Riverside scientist to conclude that these collisions likely shaped the development of Earth’s chemistry early in its history.

The team’s work is detailed in a recent Nature Geoscience article.

Impacts by asteroids or comets during the earliest years of Earth’s history likely contributed to the beginnings of life and its early evolution, yet later they delayed the development of more complex life forms that require oxygen.

“Asteroid impacts can enhance the release of gases from the Earth that consume oxygen,” explained research team member and UCR biogeochemistry professor Tim Lyons.

“In addition, it’s common for meteorites to contain large amounts of iron that can interact with water and generate gases that affect the composition of the atmosphere,” he said.

For example, iron can increase the flux of hydrogen and methane, both of which consume oxygen.

The revised understanding of our atmosphere is based on recent discoveries in Earth’s crust that point to a frequency of impacts roughly 2.4 to 3.5 billion years ago that greatly exceeds previous estimates.

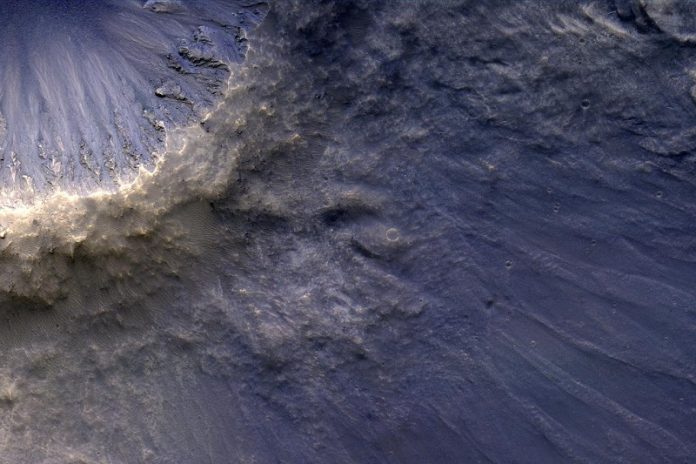

When large asteroids or comets struck, energy was released and it vaporized rocky materials in the planet’s crust. Small droplets of molten rock in the impact plume condensed, solidified, and fell back to Earth, creating round, sand-sized particles.

These particles, or impact spherules, are markers of ancient collisions. “In recent years, a number of new spherule layers have been identified in drill cores and outcrops, increasing the total number of known impact events during the early Earth,” said Nadja Drabon, a Harvard University professor and research team member.

The research team, led by Simone Marci at Southwest Research Institute, found that the impacts tapered off around 2.4 billion years ago. This reduction coincided with a major shift in surface chemistry triggered by the rise in atmospheric oxygen, dubbed the Great Oxidation Event.

“For eons, there was a dance between the rise and fall of oxygen before it became a permanent feature of our atmosphere,” Lyons said. “Then, finally, the balance tipped for a number of reasons, one of which was the declining frequency of impacts.”

Readers need not be concerned about the re-emergence of an era in which we are again bombarded by giant asteroids.

Impacts are far less common over the second half of Earth’s history. And while there are thousands of near-Earth objects today, some with the potential to hit Earth, the vast majority are quite small, and NASA closely monitors the larger ones.

Remarkably, though, impacts played a major role in shaping the history of life on Earth over billions of years.

In addition to affecting oxygen, they caused major extinction events and changed the composition of the atmosphere in ways that warmed Earth’s surface and triggered the formation of organic molecules that likely served as the initial building blocks of life.

Impacts were particularly large and frequent in our early history. As the frequency and size of extraterrestrial object impacts declined, their ability to hold back the accumulation of oxygen in the atmosphere also declined, contributing to the initial rise of oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere roughly 2.4 billion years ago.

“This change,” Lyons said, “set the stage for the complex, oxygen-requiring life that followed, including the first animals more than a billion and a half years later.”

Written by Jules Bernstein.