Quantum physics has demonstrated that tiny particles can exist in multiple places at once, but a new method may prove that it is possible for larger, visible objects to also exist in multiple places.

Physicists have been investigating this possibility for almost a century, and now a University of Queensland-led international collaboration has suggested that a tiny heat-seeking tool may finally provide the answer.

UQ’s Dr Stefan Forstner said the result could turn our understanding of physics on its head.

“Quantum superposition – the quantum effect where particles exist concurrently in multiple places – has, historically speaking, only been thought to apply to tiny, subatomic particles,” Dr Forstner said.

“But superposition of larger, visible objects may in fact be possibly, unless – as theory suggests – a background noise field exists, which would simultaneously prevent such macroscopic quantum states and create tiny amounts of heat.

“This could be a smoking gun, which would rule out larger-scale superposition – but, for the last century, we haven’t observed this evidence.

“So far, experimental proof has failed to find this incredibly small amount of heat, which is much smaller than the heat found in even the coldest fridges.

“And it can also be distorted even by the miniscule amount of heat that is introduced through measurement.

“By using a recently developed nanometre-sized resonator – that’s essentially insensitive to the environmental temperature – together with a clever measurement strategy, we can avoid these problems.”

When quantum mechanics was first discovered in the 1920s and 1930s, there was a lot of debate about linear superposition – where objects can exist is several, spatially separated positions at once.

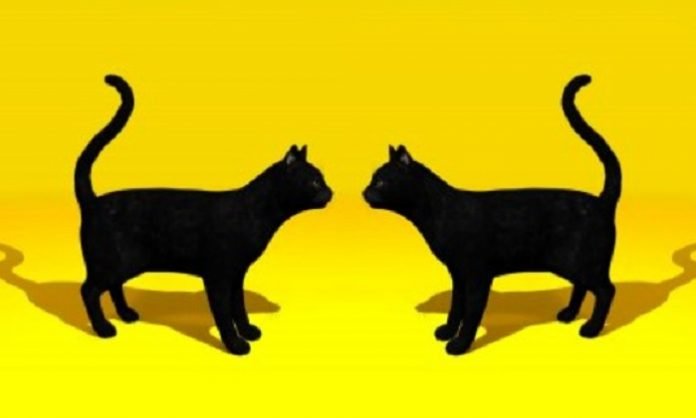

Senior author Professor Warwick Bowen said debate between physicists about this quantum phenomenon led Schrödinger to develop his famous example of the cat, which according to quantum mechanics could be alive and dead at the same time.

“The discussions finally settled for the Copenhagen Interpretation, which states quantum mechanics is just a tool to describe those tiny atoms and molecules, but can never describe the ‘real’ world as we know it,” Professor Bowen said.

“It turns out they were wrong.”

Over the past 20 years, experimentalists have created quantum states in objects of trillions of atoms – large enough to be seen with the naked eye.

Despite this, they have yet to show that linear superposition can occur with objects of this size.

“When you look at the known laws of physics, there’s no fundamental mechanism to stop us from creating quantum states of larger and larger objects, or even living beings,” Dr Forstner said.

“So we have to ask the question – is there a still unknown mechanism that stops us from creating ever larger quantum states?

“Or, as we advance our technological abilities, can we hope or fear, to one day make Schrödinger’s cat a reality?

“It’s a finding that would make us all question our reality.”

The research has been published in Optica