Who needs a free naloxone kit?

Just about anyone who might come across an opioid overdose, according to a range of University of Alberta experts.

Alberta Health Services first made the kits and training available for free to the general public in January 2016 through pharmacies, treatment centres and hospitals.

Since then nearly 200,000 kits have been handed out and a reported 12,830 have been used to halt an overdose.

During the same time period, opioid-related deaths have stabilized at roughly two per day in the province, but Emergency Medical Services in Alberta have noted a doubling of opioid-related calls since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Naloxone is one of the most effective interventions that we have for reducing overdose deaths,” said Elaine Hyshka, an assistant professor at the U of A’s School of Public Health.

Mason Schindle, a neuroscience student who founded the The FentaNIL Project last year, a campus club that hands out naloxone kits to students and trains them on how to use the kits, lost a friend in high school when synthetic opioids were becoming more widely available.

“I also have a family member who has been battling a fentanyl addiction on and off, and the only reason that individual is still alive is because of naloxone,” said Schindle.

“94% of overdose deaths happen by accident,” said Aron Walker, a pharmacist who manages the University Health Centre Pharmacy and was teaching a monthly course on campus on how to use the kits until the classes were temporarily suspended due to COVID-19.

“For people who say, ‘I don’t need a naloxone kit, I don’t use opioids, this crisis does not affect me’—those statements are becoming less and less true.”

“Most deaths are people with substance use disorder who accidentally take too much,” Walker added. “A portion are people using other illicit drugs that are adulterated.

And a very small percentage of people who overdose are people who have accidental contact, such as prison guards, first responders, police or children who are in homes where someone is cooking drugs.”

Why it’s so easy to overdose on opioids

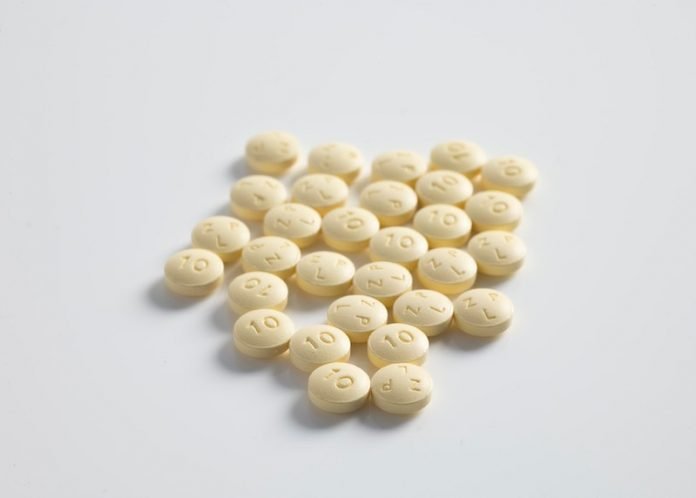

Opioids are synthetic drugs such as codeine, morphine, heroin, oxycodone, methadone, fentanyl and carfentanil—all based on the chemical structure of the opium poppy.

In a medical setting they are used as painkillers, but people who use illegal drugs seek them out for their euphoric effects.

They also depress the central nervous system, which means they reduce consciousness level and the ability to breathe.

Walker explained to his class that fentanyl is 100 times more potent than morphine, and carfentanil, originally developed as an animal tranquilizer, is 1,000 times more potent than morphine, so it is easy to take too much in a non-medical setting.

The other reason for so many overdoses, said Walker, is a lack of quality control in illegal drug manufacturing, which leads to uneven amounts of the active ingredient in each dose.

“I compare it to making chocolate chip cookies,” said Walker. “No matter how well you mix your batter, you’re gonna get some cookies that have more chocolate chips and some cookies that have less.”

Naloxone is a “competitive antagonist,” meaning it kicks the opioids off the receptors in the body that would normally react to the drug.

Once naloxone has been administered, the opioids continue to float around in the blood system, with nowhere to act.

What’s in the kit and how to use it—even during COVID-19

Walker said naloxone is harmless, so if you think you are witnessing an overdose (see sidebar) and you have a kit, don’t hesitate to administer it.

That said, it can be intimidating to use for a person with no medical background.

That’s why the free kits come with simple instructions, created by U of A design studies assistant professor Gillian Harvey, and mandatory training, which can take anywhere from 10 minutes to an hour.

“We don’t expect you to look like they do on ‘Grey’s Anatomy,'” he said. “You’re going to be shaking, you might fumble a little bit, you might do a couple of steps wrong.That’s OK. Any intervention you make is a positive step.”

First, try and wake the person up by talking loudly and rubbing their chest with your knuckles. If there’s no response, call 911.

It’s important to call for medical help right away, because even if naloxone revives the person, the half-life of opioids in blood can be longer than that of naloxone, so the overdose can happen again.

The first piece of equipment you will need from the kit is not the naloxone, it’s the breathing mask.

Oxygen is the first line of defence during an overdose, so in normal times, it’s recommended to begin rescue breathing right away.

The one-way adapter is meant to provide a barrier between the responder and the person receiving aid, but it is unknown whether it can help prevent COVID-19 infection, so Alberta Health Services advises that people wear personal protective equipment if it is available, and to carry out rescue breathing or CPR at their own discretion.

If you choose not to provide rescue breathing, you can still administer naloxone.

“Oxygen is key to life, so that’s why it’s so important if you have a naloxone kit to get trained,” said Hyshka.

“You’ll learn not just how to administer naloxone, but also how to safely provide rescue breathing. That is a core component of overdose response—it’s not just giving someone a shot.”

Pinch the nostrils and breathe forcefully through the adapter. Let go, watch the chest fall, then do it again for about two minutes, or 24 breaths.

If there’s still no response, then you administer the naloxone. Draw a full vial up, avoiding air bubbles, then push the needle straight into the thigh.

The naloxone will take two to five minutes to kick in, so it’s important to do another two minutes of rescue breathing immediately.

Continue the cycle until the person starts breathing on their own, you’ve used up all three vials of naloxone or medical help arrives.

Opioids on campus

It’s not known how many of Alberta’s post-secondary students use opioids, but 19 campuses have been targeted by the Alberta government for an opioid awareness campaign because they are considered an at-risk demographic.

Students are unlikely to reliably report drug use or naloxone reversals because of the stigma, according to Hyshka. She expects the number of lives saved by naloxone is vastly under-reported.

Marcel Roth, director of U of A Protective Services, said he’s had reports of naloxone being used to revive people on campus only three times since 2018, all administered by emergency services personnel for people who were not students or staff.

Roth’s 20-member security squad carry naloxone spray when on duty and he encourages regular citizens to get a kit and be ready.

“You can come across an emergency in your workplace or in your personal life,” Roth said.

“It’s probably the same conversation that people had years ago about taking CPR training or carrying emergency gear in their vehicles. It’s just a good idea.”

Schindle, a fourth-year neuroscience student who hopes to study rural medicine, has just received a Healthy Campus Unit Heroes for Health grant to develop and add a fentanyl testing kit to the naloxone packages his volunteers distribute, so drug users can test for the presence of fentanyl in their drugs before they take them.

“It’s not like 50 percent of students on campus are using opioids,” Schindle said. “But there are definitely some students using opioids.

“Our aim is better safe than sorry. We’d rather provide the kits and never have to use them than there be a circumstance where they need them and they don’t have them.”

There is robust evidence supporting the public health benefits of the free naloxone kits, Hyshka said.

She urges anyone who uses drugs, loves someone who uses drugs, is prescribed high doses of opioids for pain relief, or lives and works in a community or setting where they are likely to encounter someone using drugs, to get a naloxone kit and learn how to use it.

For Lia Firth, a pharmacy grad who works in medical microbiology and immunology, taking the naloxone kit course was something she’d been meaning to do for a while.

“I have a friend whose niece passed away from an overdose at a party,” she said. “It was pretty shocking for her entire family.

With my pharmacy background I learned about drug abuse, but I’ve never used a naloxone kit before. That incident was the catalyst for me.”

Education student Ryan Williams said he has never witnessed an overdose but wants to be ready.

“I know people who use drugs and I don’t want to see them die,” he said. “I intend to keep the kit with me, especially when I go to places where I know or suspect that people are using drugs.”

“I usually pack a backpack that’s got snacks or a game or a bottle of wine, and now I’ll include my naloxone kit too.”

Signs and symptoms of an opioid overdose

Slow breathing or no breathing

Unresponsive to voice or pain

Pale face

Lips or nails appear blue

Gurgling or snoring sounds

Choking or vomiting

Cold and clammy skin

Constricted or tiny pupils

Seizure-like movement or rigid posture

Written by Gillian Rutherford.