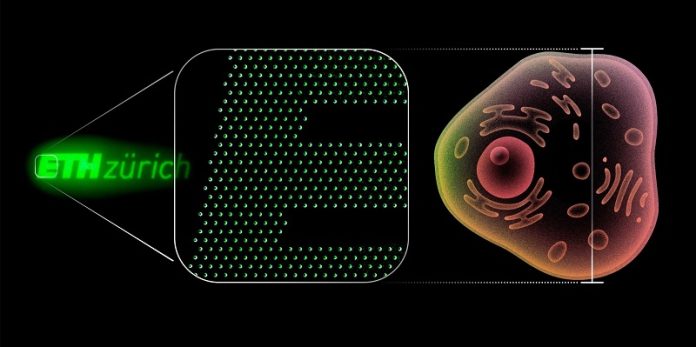

Researchers at ETH Zurich have created some of the smallest light-emitting diodes ever made—so tiny that thousands of them could fit inside a single human cell.

These miniature organic LEDs, or nano-OLEDs, represent a major leap forward in how small and powerful display and optical technologies can become.

The work, published in Nature Photonics, could lead to ultra-high-resolution screens, new types of microscopes, faster data transmission, and even futuristic 3D holographic displays.

Light-emitting diodes, or LEDs, convert electricity into light. Traditional OLEDs are used in today’s high-end smartphones and TVs, but researchers have now shrunk them by several orders of magnitude.

The smallest pixels created so far are only about 100 nanometers wide—roughly 50 times smaller than the best commercially available OLED pixels. Doctoral student Jiwoo Oh and postdoctoral researcher

Tommaso Marcato developed a method that makes it possible to create these nano-OLEDs in a single manufacturing step. This breakthrough boosts the maximum pixel density by as much as 2,500 times.

This extreme miniaturization opens the way for new applications. A screen made from such tiny pixels could display incredibly sharp images even when viewed extremely close to the eyes, such as in next-generation smart glasses.

The research team demonstrated this by creating a tiny ETH Zurich logo made from 2,800 nano-OLEDs—yet the entire image was about the size of a human cell. Microscopes could also benefit from these mini-pixels.

A pixel array could illuminate very small regions of a sample one at a time, enabling images far more detailed than what is possible today.

Because the pixels are smaller than the wavelength of visible light, they can be arranged close enough for their light waves to interact with each other.

Normally, two light waves only combine or interfere when they are at least half a wavelength apart.

Nano-OLEDs break this barrier. When placed extremely close together, their emitted light can reinforce or cancel out neighboring waves, similar to how ripples in a pond interact when you toss in two stones.

By arranging the pixels intelligently, researchers can control the direction in which light travels, producing beams that emerge only at specific angles instead of spreading in all directions.

This controlled interference allows the pixels to generate polarized light, which vibrates in just one direction. Polarized light already has important uses in medical imaging, helping doctors distinguish healthy and damaged tissue. In the future, controlled nano-OLED arrays might be used in advanced optical devices, sensors, or even miniature lasers.

A key part of the breakthrough came from using an extremely thin and strong ceramic material called silicon nitride. It can form membranes that are only a few thousandths the thickness of materials used in today’s OLED manufacturing techniques. Because these membranes are so thin and stable, they allow precise placement of nano-sized light pixels and can be integrated directly into the standard processes used to produce computer chips.

The ETH Zurich team is now working on ways to individually control each nano-OLED, which would allow them to fully harness the interactions between pixels.

Their long-term goal is to create “phased array optics,” where light beams can be steered electronically, much like modern radar systems steer radio waves.

Eventually, these arrays could create true holographic displays. Instead of flat images, future screens might project 3D visuals that surround viewers in space, offering a glimpse of what the next generation of optical technology may look like.