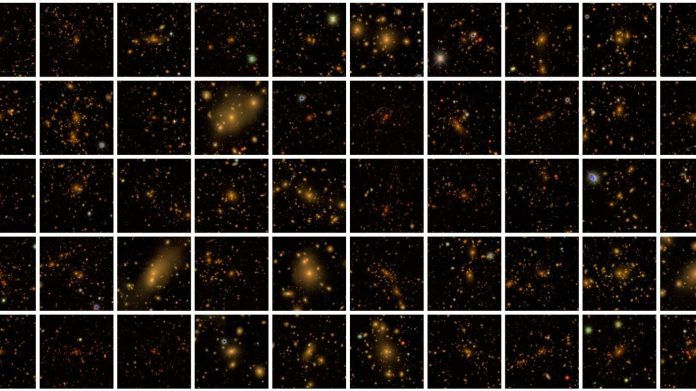

clusters of galaxies.

These gigantic structures, which contain hundreds or even thousands of galaxies bound together by gravity, offer important clues about how the universe formed and what forces shape it today.

The new analysis, released on the arXiv preprint server, uses data from the Dark Energy Survey—a six-year project based in Chile that mapped a large portion of the southern sky.

Led by researchers at the University of Chicago, the team set out to test a key question in modern cosmology: Does our current model of the universe, known as the Lambda-CDM model, still hold up under careful scrutiny?

This model includes dark matter (which pulls galaxies together), dark energy (which pushes the universe apart), and normal matter like stars and gas.

It has been the leading theory for decades, but some earlier studies hinted at possible inconsistencies.

One such concern is known as the “S8 tension,” a debate about how “clumpy” the universe is today compared with predictions from the early universe.

Some measurements suggested the universe might have less structure than expected, which could mean the Lambda-CDM model needs updating. Galaxy clusters are a powerful way to test this because they sit at the crossroads of dark matter and dark energy influences.

Their number, size, and distribution across the sky can reveal the underlying rules that govern cosmic evolution.

The new analysis, however, finds no cracks in the standard model. According to first author Chun-Hao To, the results show that the Lambda-CDM model describes the universe well.

Their calculations of S8 match the values inferred from the cosmic microwave background, the leftover radiation from the early universe. This strengthens confidence that the standard model is still accurate.

To reach these conclusions, the researchers had to carefully account for several challenges. Galaxy clusters can sometimes overlap in the line of sight or appear distorted because of observational limitations.

If not corrected, this could make clusters seem fewer or smaller than they really are—leading to incorrect estimates of dark matter. But Chihway Chang, a senior author of the study, says the team developed methods to adjust for these issues and achieve a clearer, more reliable census of galaxy clusters.

Understanding these clusters is also important because they help scientists study dark matter and dark energy, two mysterious components that make up 95% of the universe. Dark matter helps bind galaxies together, while dark energy drives the acceleration of cosmic expansion. Because clusters are so massive, their behavior offers a strong signal of how these invisible forces operate.

The new findings come at a perfect time. In the next few years, powerful new telescopes such as the Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time and NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will begin scanning the sky. These observatories will detect far more galaxy clusters than ever before, giving scientists an unprecedented view of the universe’s structure.

Each new cluster is another data point—and potentially another clue—to understanding the cosmos. As noted, the study provides a strong foundation for future research and a new angle for exploring some of the biggest questions in astronomy.

Source: University of Chicago.