Scientists have developed a new kind of brain-computer interface (BCI) that is so small and thin it can slide gently between the skull and the brain—almost like a sheet of wet tissue.

Despite its tiny size, this implant can send and receive huge amounts of information, opening the door to treatments for neurological conditions such as epilepsy, ALS, paralysis, stroke, and even certain forms of blindness.

It may also one day allow people to communicate directly with computers and artificial intelligence systems without wires or bulky equipment.

This new platform is called the Biological Interface System to Cortex, or BISC. It was developed by researchers from Columbia University, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, Stanford University, and the University of Pennsylvania.

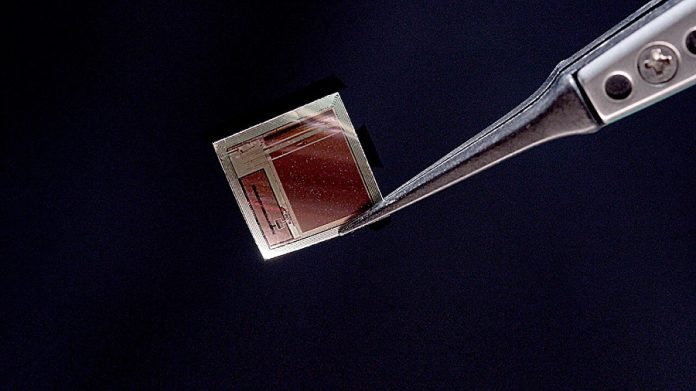

Their work is described in Nature Electronics. What makes BISC groundbreaking is its simple design: a single silicon chip that serves as a complete neural interface.

Traditional BCIs require a large canister filled with electronics—amplifiers, transmitters, converters, and other components—which must be implanted either inside the skull or elsewhere in the body with wires running to the brain.

Compared to those systems, BISC is dramatically smaller, safer, and faster.

The entire BISC implant is only about 50 micrometers thick—thinner than a human hair—and takes up less than one-thousandth the volume of current clinical devices.

It contains 65,536 electrodes for sensing brain activity and thousands of channels for recording and stimulation.

Despite being so small, it includes everything needed to function on its own: a radio system for wireless communication, circuitry for powering and controlling the device, and the ability to both read electrical signals from the brain and send signals back in.

The implant sits directly on the brain’s surface, molded gently to its curves.

A separate battery-powered wireless relay station is worn on the outside of the body.

It powers the implant and communicates with it using an ultrawideband radio link capable of transmitting data at 100 megabits per second—more than 100 times faster than any current wireless BCI. That station then connects to any computer through WiFi, forming a bridge between the brain and external devices.

This high-speed connection allows researchers to send brain data to advanced machine-learning and artificial-intelligence systems.

In demonstrations, BISC accurately decoded complex patterns of neural activity, showing how it could help restore speech, movement, or vision for people with neurological damage. Because the implant does not penetrate the brain and has no wires anchoring it to the skull, it is designed to minimize tissue irritation and maintain stable recordings over time.

To bring this technology closer to real-world use, the Columbia team partnered with neurosurgeons to refine the surgical technique. The implant can be inserted through a small opening in the skull and gently slid into place beneath the bone. Early tests in preclinical models have confirmed the device’s stability and high-resolution performance. Human studies for short-term recordings during surgery are already underway, offering valuable insight into how BISC behaves in real clinical environments.

The collaboration behind BISC combines microelectronics expertise, cutting-edge neuroscience, and innovative surgical techniques. It was initially supported by the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). A new company, Kampto Neurotech, has been formed to turn BISC into commercial products for research and eventually medical use.

Researchers believe this technology represents a major step forward for the field.

By creating a fully wireless, ultra-thin, high-bandwidth interface, they are moving toward a future where people with neurological conditions can regain lost abilities—and where healthy individuals may someday interact directly with AI and digital devices through thought alone.

According to the team, BISC could redefine how we treat brain disorders, how humans control machines, and how we connect with technology in everyday life.