Astronomers have captured the most detailed close-up images ever taken of stars exploding, known as novae.

These pictures were taken within days of the eruptions and show that the explosions are far more complicated than scientists once believed.

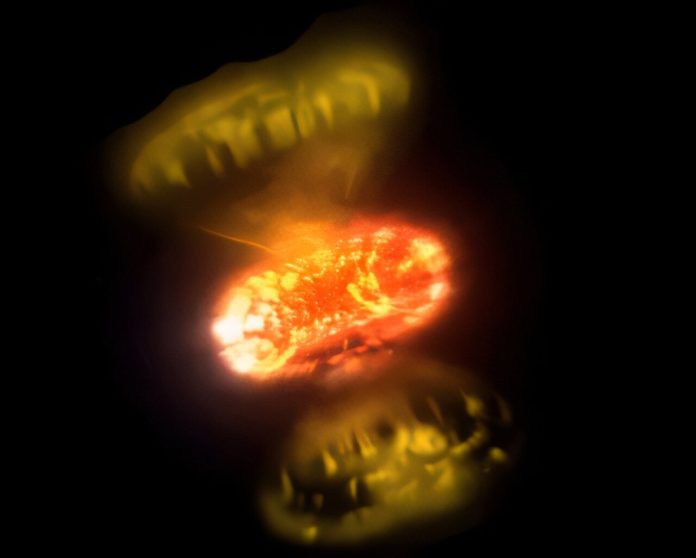

Instead of a single burst of material, the new images reveal multiple streams of gas, unexpected delays in the ejection process and dramatic collisions happening in real time.

The breakthrough is described in a new study published in Nature Astronomy.

To make these images, researchers used an advanced technique called interferometry at the Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA Array) in California.

This method combines the light from several telescopes to create images sharp enough to see fast-changing structures around exploding stars.

According to Gail Schaefer, director of the CHARA Array, the team had to be ready to switch observing targets quickly, since novae erupt without warning and fade rapidly.

A nova occurs when a white dwarf—the dense, burned-out core of a once normal star—pulls material away from a nearby companion star.

When enough stolen material builds up, it triggers a runaway nuclear explosion on the white dwarf’s surface. For decades, astronomers could only observe these eruptions as a single bright point of light, making it impossible to see the early details of how the explosion unfolded.

Understanding the shape and motion of the ejected material is important because novae produce shock waves that create high-energy gamma rays.

NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope has detected these gamma rays from more than 20 novae over the past 15 years, showing that they are powerful sources of radiation. Until now, the exact origin of these shocks was unclear.

The new study focused on two very different novae that erupted in 2021. The first, Nova V1674 Herculis, was one of the fastest ever recorded.

It brightened and faded in just a few days. Images showed two distinct flows of gas shooting out in perpendicular directions, revealing that the explosion involved several interacting outbursts, not a single blast.

Even more remarkable, these gas flows appeared at the same time that NASA’s Fermi telescope detected gamma rays, providing direct evidence that the shocks powering the radiation were caused by colliding outflows.

The second nova, V1405 Cassiopeiae, behaved very differently. Instead of ejecting material immediately, it held onto its outer layers for more than 50 days—something that had never been clearly seen before. When it finally released this material, new shock waves formed and again produced gamma rays detected by Fermi. This slow eruption showed that nova explosions can evolve in ways that were previously hidden.

Lead author Elias Aydi of Texas Tech University says the improvement in clarity is like going from a grainy black-and-white photograph to high-definition video. The interferometric images were matched with detailed spectra from observatories such as Gemini, which showed the chemical fingerprints of gas moving at different speeds. As new structures appeared in the images, they matched perfectly with new features in the spectra, giving scientists a direct way to connect the shapes they saw with the physics behind them.

According to co-author John Monnier of the University of Michigan, the ability to watch a stellar explosion as it happens marks an extraordinary leap in astronomy. It also changes the long-standing idea that novae are simple, single events. Instead, novae appear to involve a variety of ejection patterns, multiple interacting flows and sometimes long delays before material is released.

Researchers say these discoveries will help answer bigger questions about how stars evolve and how their explosions shape the environments around them.

As Professor Laura Chomiuk of Michigan State University explains, novae act as natural laboratories for extreme physics. With more real-time images, scientists will be able to uncover even more about these dramatic and surprisingly complex cosmic blasts.