Clouds may spoil a picnic or block our view of the stars, but they could also help scientists discover life on distant planets.

A new study from Cornell University shows that the colorful microorganisms floating high above Earth might offer important clues for detecting life in the cloudy atmospheres of exoplanets.

For the first time, researchers have created reflectance spectra—a kind of color map—of different microorganisms that live in Earth’s upper atmosphere.

These tiny life forms, including bacteria with bright pigments, exist high above the surface, though they are rare.

Even if they are not common enough on Earth to be seen from space, their colorful signatures could help astronomers spot similar microbes elsewhere in the universe.

Astrobiologist Ligia Coelho, a 51 Pegasi b Postdoctoral Fellow in Cornell’s College of Arts and Sciences and the Carl Sagan Institute, led the study. She explained that Earth’s atmosphere hosts a surprising community of microbes that produce striking pigments.

These pigments protect them from harsh conditions, such as intense ultraviolet radiation and extreme dryness. Because these colors reflect light in unique ways, they can create signals that telescopes might detect on other planets.

Published on November 11 in Astrophysical Journal Letters, the study provides a new set of tools for astronomers. Coelho and her team collected samples of seven different bacteria from the lower stratosphere, between 21 and 29 kilometers above the Earth’s surface.

The samples were gathered using a latex balloon by collaborator Brent Christner from the University of Florida, whose previous research has shown that some microbes survive at altitudes up to 38 kilometers.

Once collected, the bacteria were grown in the lab and analyzed to measure how they reflect light. These measurements revealed unique color signatures that could function as biosignatures—clues that point to the presence of life. The researchers then modeled how a planet covered in clouds filled with such colorful microbes would appear from afar. They found that the planet’s reflected light would look noticeably different from a lifeless cloudy world.

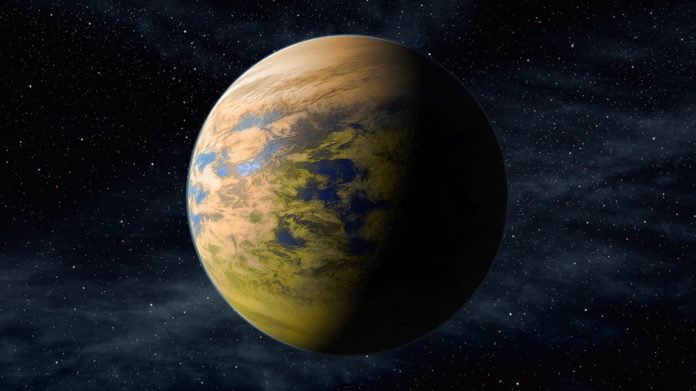

This means that clouds, once thought to hide signs of life, might actually make them easier to detect. If exoplanets have humid, cloudy atmospheres that support airborne microbes in large numbers, future telescopes might be able to identify their colorful pigments.

These findings are already shaping the design of next-generation observatories, including NASA’s upcoming Habitable Worlds Observatory and the European Southern Observatory’s Extremely Large Telescope, expected to begin observations in the 2030s.

Coelho says that pigments are universal tools used by many life forms—plants, animals, and even tiny bacteria—to survive challenging environments. By studying these pigments in our own sky, scientists now have a new way to search for life hidden in the clouds of distant worlds.