The strange gullies etched into the red sands of Mars have long puzzled scientists.

Were they carved by running water, avalanches, or perhaps even traces of ancient life?

According to new research, the answer is far more unusual — and has nothing to do with life. Instead, the gullies appear to be carved by blocks of carbon dioxide (CO₂) ice that burrow into the sand like living creatures.

Dr. Lonneke Roelofs, an Earth scientist at Utrecht University, has recreated this bizarre Martian phenomenon in a laboratory and watched it happen for the first time.

“It felt like I was watching the sandworms from Dune,” she said.

Her findings, published in Geophysical Research Letters, reveal that chunks of CO₂ ice — often called “dry ice” — can dig deep channels as they slide down Martian dunes.

On Mars, winter temperatures can plunge below minus 120 degrees Celsius, cold enough for carbon dioxide from the thin atmosphere to freeze into ice.

As spring returns, sunlight warms the dunes, and slabs of CO₂ ice — sometimes a meter wide — break off from the surface. Because the ground is much warmer than the ice, the bottom of each block instantly begins to vaporize in a process known as sublimation, turning solid ice directly into gas.

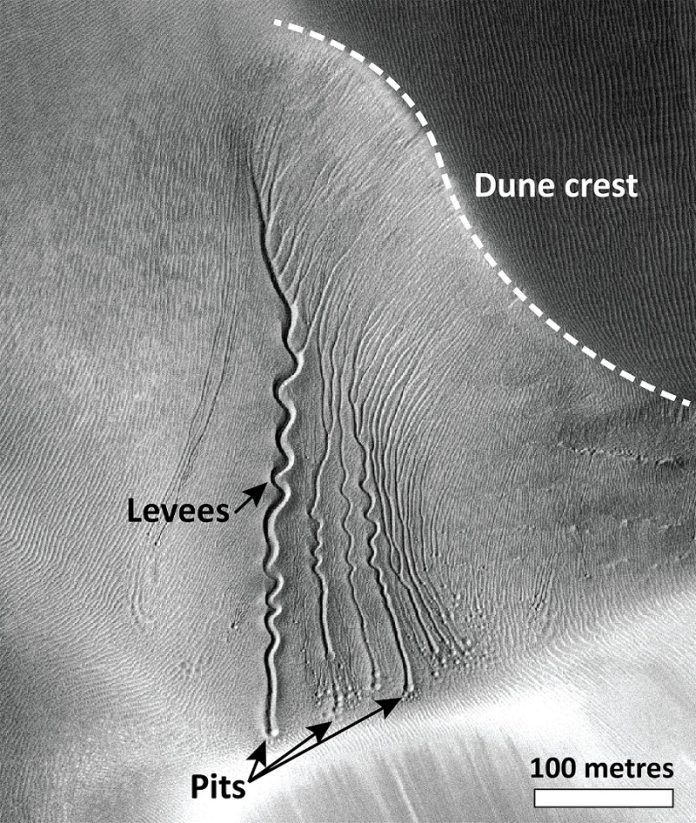

This transformation produces a powerful jet of gas that blasts sand away from beneath the block. “In our experiment, I saw how this high gas pressure blew the sand out in all directions,” Roelofs said. The ice block then burrows into the slope, forming a small hollow surrounded by ridges of piled-up sand. As the sublimation continues, the block keeps digging downward, sliding deeper and deeper, leaving behind a long, narrow trench with raised edges — just like the gullies seen on Mars.

Roelofs and her colleague, master’s student Simone Visschers, conducted their experiments at the Open University in Milton Keynes, England, which houses a special “Mars chamber.” This facility can mimic Martian conditions, including its freezing temperatures, low air pressure, and dusty terrain. The researchers placed blocks of CO₂ ice on simulated dune slopes and observed what happened.

“Once we found the right slope, the block started to dig into the sand and move downward — almost like a burrowing mole,” Roelofs said. “It was a very strange sight.”

On Mars, these events take place mainly in the southern hemisphere, where large fields of dunes are coated each winter with a thick layer of frozen CO₂, up to 70 centimeters deep. As the season warms, the ice begins to crack and slide, forming isolated blocks that tumble down slopes. Once they reach the bottom, the remaining ice continues to sublimate until it disappears completely, leaving a hollow in the sand as the only trace of its movement.

The results explain how Mars’s mysterious gullies form without liquid water — and why they appear to have been “dug” rather than eroded.

For Roelofs, studying such alien processes also offers insight into our own planet. “Mars is our nearest neighbor and the only rocky planet near the zone where liquid water could exist,” she said.

“By studying how its landscapes form, we learn not only about Mars, but also about the forces that shape worlds — including our own.”

Source: KSR.