It might sound like something out of science fiction: a tiny spacecraft, no heavier than a paperclip, launched from Earth and traveling at a third of the speed of light toward a black hole.

But according to astrophysicist Cosimo Bambi, this bold mission could become a reality within the next few decades—and it could help us test the very limits of physics.

In a recent paper published in iScience, Bambi, a black hole expert at Fudan University in China, outlines a plan for sending an interstellar probe to a nearby black hole.

If successful, the mission could return data that reshapes our understanding of Einstein’s general theory of relativity and the strange physics that governs the universe’s most extreme environments.

“We don’t have the technology right now,” Bambi admits. “But in 20 or 30 years, we might.”

The mission would rely on two major breakthroughs: first, identifying a black hole close enough to reach within a human lifetime, and second, developing the kind of ultra-light, high-speed probe needed to get there.

Although black holes don’t emit or reflect light, making them difficult to detect, astronomers are getting better at finding them by observing how they affect nearby stars or bend light around them.

Based on how stars age and die, scientists believe there could be a black hole just 20 to 25 light-years from Earth. Bambi is optimistic that newer techniques could uncover one in the next decade.

To reach it, traditional spacecraft won’t cut it. Rockets that use chemical fuel are far too slow and heavy.

Instead, Bambi points to the idea of a “nanocraft”—a gram-scale spacecraft consisting of a small computer chip attached to a thin light sail. Using powerful lasers from Earth, scientists could blast the sail with light, propelling it to speeds of up to a third of the speed of light.

At that speed, a craft could reach a nearby black hole in about 70 years. The data it collects would take another 20 years to get back to Earth.

That means a full mission—from launch to receiving data—would take roughly 80 to 100 years.

Once near the black hole, the probe could help answer some of science’s deepest questions: Do black holes really have event horizons? Do the known laws of physics break down under such extreme conditions? Does general relativity still hold?

While the project would be expensive—the lasers alone would cost around one trillion euros today—Bambi believes technology and costs may improve over time.

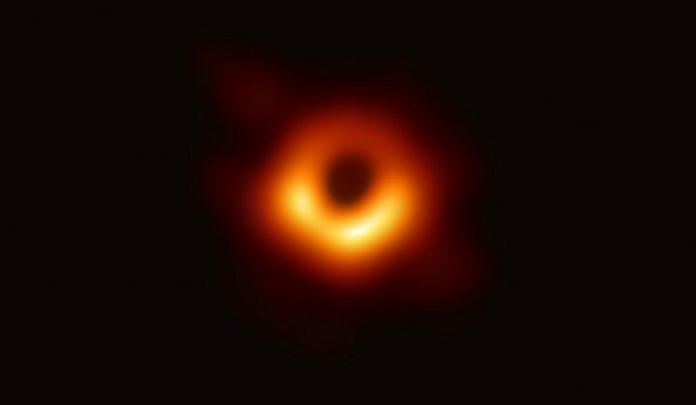

“It may sound crazy now,” he says, “but people once said the same thing about detecting gravitational waves or imaging black holes. And we’ve done both.”

Source: Cell Press.