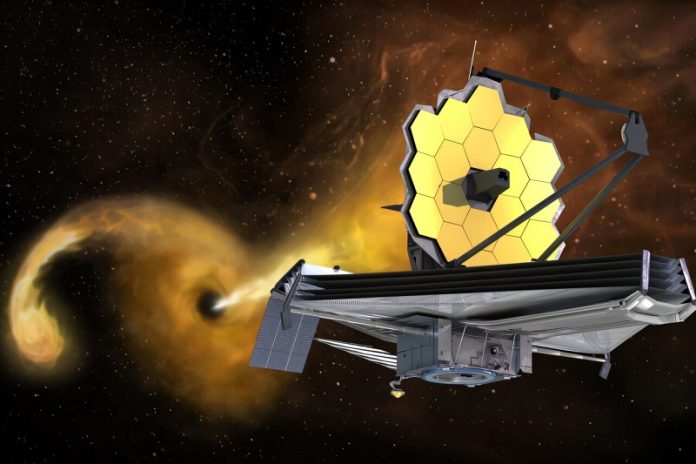

Astronomers have used NASA’s powerful James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to uncover black holes secretly devouring stars in galaxies full of dust.

These violent star-shredding events, known as tidal disruption events (TDEs), had gone unnoticed before because thick dust clouds in their host galaxies hid the signs from traditional telescopes.

In a new study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, researchers from MIT, Columbia University, and other institutions confirmed that JWST has detected clear signs of black hole activity in four dusty galaxies.

When a star gets too close to a black hole, the black hole’s gravity tears the star apart.

This creates a glowing disk of hot gas and releases a massive burst of energy.

Until now, most of these events were only seen in galaxies without much dust because their light is blocked in dusty environments. But JWST sees infrared light, which can pass through dust and reveal what’s hidden.

The researchers had previously found hints of 12 possible TDEs using NASA’s NEOWISE infrared telescope.

These were brief flashes of infrared light in quiet galaxies—potential clues that a black hole had suddenly awakened to eat a passing star.

With JWST, they took a closer look at four of these events and confirmed that each showed a distinct infrared “fingerprint” caused by black hole accretion, the process where material spins around a black hole before falling in.

In one case, the TDE happened just 130 million light-years away, making it the closest one ever detected. Another event also gave off X-rays, while a third showed signs of gas spinning rapidly near a black hole. The fourth was previously mistaken for a supernova but turned out to be a black hole feeding frenzy.

To confirm these were truly one-time events and not signs of already active black holes, the team studied the dust surrounding them. Active black holes typically have a clumpy, donut-shaped ring of dust. But these four galaxies didn’t show that pattern, suggesting the black holes were usually dormant and only lit up because of the TDE.

Lead author Megan Masterson, a graduate student at MIT, said this is the first time JWST has observed TDEs, and they look completely different from what scientists have seen before. These findings open up a new way to study how black holes behave, especially the ones that usually stay quiet.

The team hopes to discover many more of these hidden events using JWST and other infrared telescopes, helping to answer big questions like how long it takes a black hole to finish its meal—and what that process really looks like.