A new approach using generative AI, such as ChatGPT, is offering fresh hope to people with aphasia—a language disorder that affects speech, writing, and understanding.

Often caused by strokes or brain injuries, aphasia impacts millions of people worldwide.

Now, researchers at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) are exploring how AI can be used to support communication and improve quality of life.

One of the people benefiting from this new therapy is 50-year-old Nathan Johnston from Tasmania, who had a stroke 10 years ago.

Before using ChatGPT, he mostly relied on single-word messages and emojis. Today, with the help of AI, he’s composing full text messages, emails, and social media posts.

He describes ChatGPT as “awesome.”

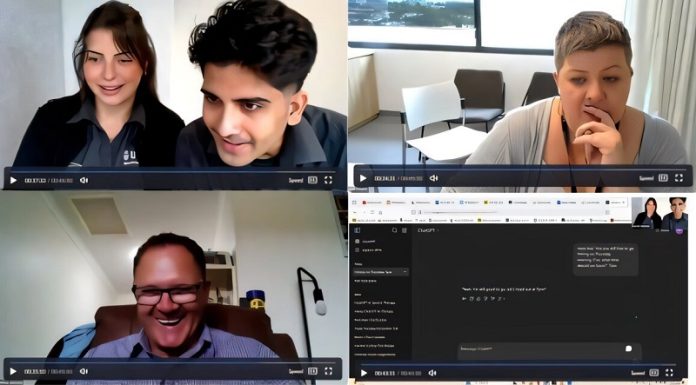

Johnston is part of the SPROUTS Clinic at UTS, a student-run program where final-year speech pathology students work with clients under professional supervision. Sessions are held online, and the service is free for participants.

Students Sarah Nehme and Muhammad Measum Ali have been working with Johnston, helping him use AI tools during weekly therapy sessions.

They guide him in using simple prompts to communicate through ChatGPT. For example, Johnston might type: “Reply text message: Did the T-shirt from Spain fit you?” ChatGPT responds with: “Yes, it fits perfectly!

Thanks again for thinking of me.” He then asks ChatGPT to make it longer, and the message becomes: “Yes, it fits perfectly! I really appreciate you thinking of me and bringing it back from Spain. It’s such a thoughtful gift, and I absolutely love it.” Johnston copies the message and sends it to his mother.

These small exchanges mark big milestones for someone with aphasia. ChatGPT, used alongside other tools like the speech-to-text app Claracom, is giving Johnston more independence and confidence in how he communicates.

Dr. Cath Gregory, a speech pathology lecturer at UTS, says the team has been testing generative AI in therapy for two years. The technology has allowed clients to reconnect with friends, join online conversations, and feel more involved in their communities. However, Dr. Gregory notes that not everyone can access or use AI tools, especially those without digital skills or reading ability.

There are also some challenges. Johnston’s mother mentioned that some people were confused by the polished tone of his Facebook posts, which sounded so different that they thought his account had been hacked. To avoid confusion, they now add “assisted by ChatGPT” to his messages.

Still, the possibilities are exciting. As AI technology continues to improve, speech pathologists hope it will become even more personalized and accessible, helping more people like Johnston find their voice again and express their identity.