Scientists have long known that sunlight is incredibly good at making water evaporate. In fact, it’s more effective than other heat sources, like your kitchen stove.

But why is sunlight so efficient?

A new study has revealed an exciting reason: the electric field that comes with sunlight might be playing a much bigger role than we thought.

The study, published in Materials Horizons, shows that the oscillating electric field in sunlight helps speed up evaporation—especially by breaking water into small groups of molecules known as “clusters.”

“Light isn’t just heat,” says Saqlain Raza, the first author of the paper and a Ph.D. student at North Carolina State University.

“It’s an electromagnetic wave, and one part of that is an electric field that constantly changes direction. That’s what we looked at in our study.”

The research team used computer simulations to understand how different aspects of sunlight affect water evaporation. When they removed the electric field from the simulation, water took longer to evaporate.

When they added the field back in—and especially when they made it stronger—evaporation happened much faster.

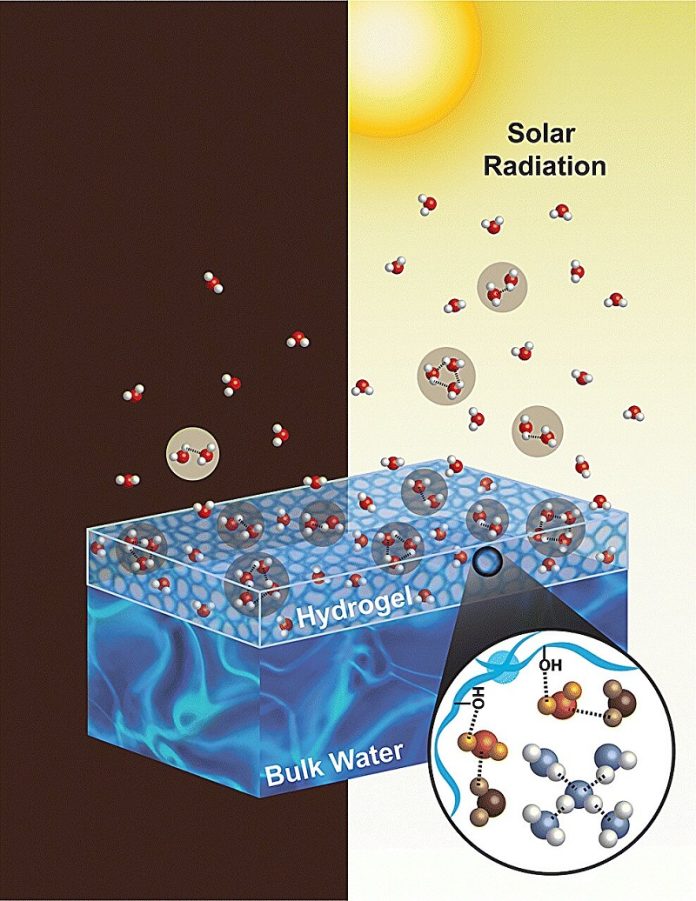

So what is this electric field doing to the water? Normally, water evaporates when individual molecules break free from the surface.

But sometimes, small groups of molecules—called clusters—escape together.

The researchers found that sunlight’s electric field is especially good at shaking loose these clusters.

And because breaking off a cluster doesn’t use more energy than breaking off a single molecule, this is a very efficient process.

To test this further, the scientists compared two situations: one with plain water, and another where water was inside a sponge-like material called a hydrogel. In the hydrogel model, more clusters formed near the surface, and evaporation happened even faster. The researchers believe this is because the electric field had more clusters to break off in the hydrogel, making evaporation quicker.

“This is the first time we’ve shown how these water clusters behave under an electric field during evaporation,” says co-author Jun Liu, an associate professor at NC State. “It changes how we understand the whole process.”

The study could help scientists design better water purification or cooling systems that take advantage of sunlight’s natural electric field. By understanding exactly how sunlight helps water evaporate, we might be able to use it more efficiently in everyday technology.

The work was done by researchers at NC State and Huazhong University of Science and Technology, and it opens a new window into one of nature’s most familiar but mysterious processes.