Iceland is one of the world’s most volcanically active places, known for its dramatic eruptions and hot springs.

But its explosive nature is just one piece of a much larger puzzle that stretches across the North Atlantic—from Greenland to western Europe—and includes ancient volcanic landscapes like the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland.

Now, thanks to a major research effort supported by the European Space Agency (ESA), scientists have uncovered new evidence about what made this entire region so volcanically active millions of years ago.

Their findings help explain not only the formation of massive volcanic areas, but also how Earth’s deep interior continues to affect earthquakes and land movement in Britain and Ireland today.

Large volcanic regions like the North Atlantic Igneous Province formed around 60 million years ago. These regions, called “large igneous provinces,” are known to have had huge impacts on Earth’s climate and life in the past.

That’s because when volcanoes erupt on such a massive scale, they release huge amounts of gases like carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere.

These gases can warm the planet or cool it temporarily, depending on how they react in the air. The lava and ash can also change the chemistry of the ocean, affecting marine life.

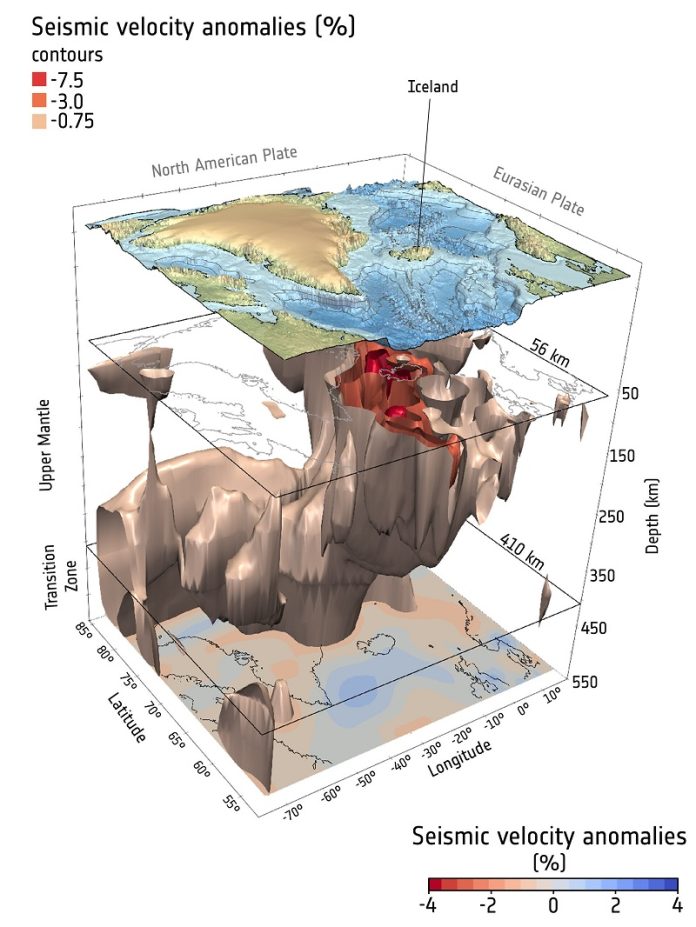

The driving force behind this volcanic activity is believed to be the “Iceland Plume”—a deep, hot column of molten rock that rises from the boundary between Earth’s core and mantle. It spreads out over thousands of kilometers and helped fuel the eruption of lava across large parts of the North Atlantic region.

Until recently, scientists didn’t fully understand why this volcanic activity was scattered across such a wide area. The answer, it turns out, may lie in how thick or thin the outer layer of the Earth—the lithosphere—is in different places.

Using data from ESA’s GOCE satellite, which measures gravity differences on Earth, researchers applied a new method to map variations in lithosphere thickness beneath Britain and Ireland.

Their results show that ancient volcanic activity—like the uplifting and eruption of lava at the Giant’s Causeway—happened in places where the lithosphere is unusually thin. This thinness allowed the hot plume material to rise more easily to the surface, triggering eruptions and shaping the landscape.

The study also found that modern-day earthquakes in Britain and Ireland tend to occur in the same thin zones, rather than along traditional tectonic fault lines. That’s because these areas are still geologically weaker and more flexible, due to the lasting effects of the ancient plume activity.

These discoveries not only solve a long-standing geological mystery but also demonstrate the importance of satellite gravity data in understanding our planet’s deep inner workings.

ESA is now working on a new mission called the Next Generation Gravity Mission (NGGM), which will give scientists an even clearer picture of how Earth’s crust and mantle behave—and how those behaviors influence everything from earthquakes to volcanic eruptions.

Source: European Space Agency.