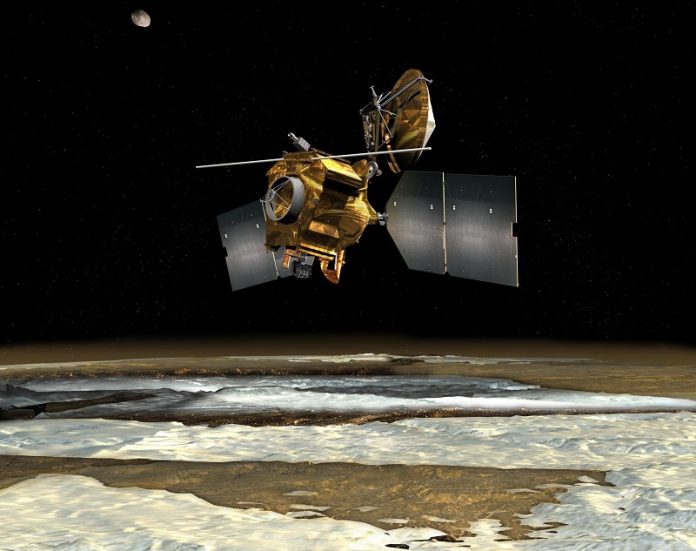

Even after nearly two decades in space, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) is proving it’s far from outdated.

Engineers have recently taught the spacecraft a new maneuver that allows it to roll almost completely upside down, helping it see much deeper beneath the Martian surface.

This move is not just impressive—it’s unlocking exciting new science on Mars.

The MRO has been circling Mars since 2006, taking high-resolution images, scanning the atmosphere, and searching for water.

One of its key tools is SHARAD (Shallow Radar), which sends radar waves down to detect materials like rock, sand, and especially ice, buried beneath the surface.

Knowing where ice is on Mars is vital for understanding the planet’s history and preparing for future astronaut missions, as the ice could be used for drinking water or rocket fuel.

Until recently, SHARAD’s view was slightly blocked because it’s located at the back of the spacecraft.

When the radar sent signals down to Mars, parts of the orbiter would get in the way, interfering with the radar waves and making the images less clear. Scientists wanted to find a way to give SHARAD a clearer view—and that’s where the new maneuver comes in.

Starting in 2023, engineers began performing what they call “very large rolls,” turning the spacecraft a full 120 degrees so SHARAD can look straight down without interference. These rolls boosted the radar’s signal strength by more than ten times, revealing much clearer images of what lies beneath the surface of Mars.

However, rolling the spacecraft this far comes with challenges. During the maneuver, MRO’s antenna can’t point at Earth, and its solar panels can’t face the Sun.

This means the orbiter has to rely on battery power, which requires careful planning to avoid running out of energy. That’s why only one or two of these rolls are done each year—at least for now.

While SHARAD is gaining better underground views, another instrument on MRO has adapted to the spacecraft’s regular, smaller rolls. The Mars Climate Sounder, which studies temperature, clouds, and dust in the atmosphere, originally had its own moving platform to help aim at targets. But in 2024, that system became unreliable due to age.

Now, the team uses MRO’s normal rolling ability to help the instrument continue its work. In fact, the new approach has become part of their regular science routine.

These rolling maneuvers are a good example of how scientists can find clever solutions to get more life and data out of older spacecraft. What began as a mission to photograph Mars has evolved into a multi-purpose observatory that continues to discover new things about the Red Planet—thanks to a few well-timed flips in space.

Source: NASA.