A team led by Cornell University has created a new technology that could help solve two major global problems at the same time: clean energy and water scarcity.

Their invention uses sunlight and seawater to make green hydrogen—a clean fuel—and, as a bonus, produces drinkable water.

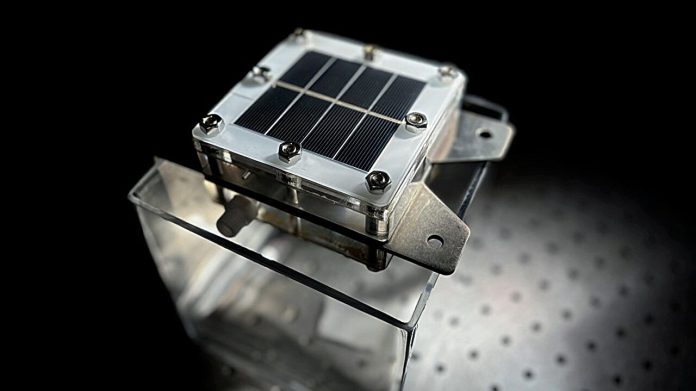

The device, called the hybrid solar distillation-water electrolysis (HSD-WE) system, is a small prototype that’s about the size of a notebook (10 by 10 centimeters). It uses solar power to split seawater into hydrogen and oxygen.

This process is called electrolysis, and it usually needs very pure water, which makes it expensive. But this new device can use regular seawater and still work well.

Right now, the prototype can produce about 200 milliliters of hydrogen per hour with an energy efficiency of 12.6%.

While that might sound small, the team believes that with time and development, this technology could cut the cost of green hydrogen to just $1 per kilogram within 15 years.

Today, green hydrogen costs around $10 per kilogram, which limits its use.

The lead researcher, Professor Lenan Zhang, explained that both water and energy are essential for daily life, but they are often hard to get at the same time.

Most green hydrogen systems use a lot of clean water, which is a problem since two-thirds of the world’s population already struggles to get enough drinking water.

That’s why this new technology is so important—it uses the most common resources on Earth: sunlight and seawater.

The device works in a clever way. Solar panels normally only turn about 30% of sunlight into electricity.

The rest becomes heat and is usually wasted. But Zhang’s team figured out how to use that heat to help evaporate the seawater.

The device has a special material called a capillary wick that holds a very thin layer of water close to the solar panel. Only this thin layer needs to be heated, making the process very efficient—more than 90% of the water evaporates.

As the seawater turns into vapor, the salt is left behind. The clean vapor then turns back into liquid water, which goes into the electrolyzer to make hydrogen. Any extra clean water can be used for drinking.

Zhang said the team is excited about how this could be used in the future, not only to make green hydrogen more affordable but also to help cool solar panels and improve their performance.

He believes the device has great potential for large-scale use in solar farms around the world, helping to fight climate change while also solving water shortages.