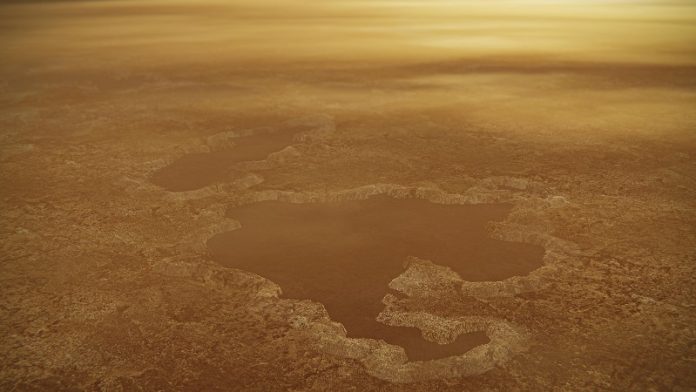

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, has long fascinated scientists with its strange and alien landscape.

Covered in rivers and lakes of liquid methane, massive ice boulders, and dark sand dunes, Titan looks like a world from science fiction.

With a thick, hazy atmosphere and a hidden underground ocean, it has often been considered a possible place where life could exist beyond Earth.

Now, a new study led by an international team of scientists—including Antonin Affholder from the University of Arizona and Peter Higgins from Harvard University—has taken a closer look at this possibility.

Their research, published in The Planetary Science Journal, focuses on whether Titan really could support life, where it would most likely be found, and how much life could actually be there.

Unlike some other icy moons, Titan is full of organic molecules—the basic building blocks of life.

This makes it especially interesting to scientists. But Affholder says that while these organics are plentiful on the surface, that doesn’t mean they are useful for life. “People often assume that because there are so many organics on Titan, there must be plenty of food for life,” he said.

“But we show that this may not be the case.”

Titan has a hidden ocean beneath its icy surface that may be around 300 miles deep. Using models of energy use in biology, the research team explored how microbes might survive in this subsurface ocean.

They focused on a simple process called fermentation, which only needs organic molecules and doesn’t require oxygen. Fermentation is a very old form of metabolism—used by yeast in bread and beer—and may have been one of the first ways life began on Earth.

The team chose to study glycine, the simplest amino acid, which is commonly found in space. If life exists on Titan, it might feed on glycine arriving from the surface.

But here’s the catch: only a small amount of glycine might reach the ocean below the thick ice, making it difficult to support much life. Simulations showed that even if microbes could survive in the ocean, the total mass of life would be very small—no more than a few kilograms, or the weight of a small dog.

That means, even if life does exist on Titan, it would be incredibly hard to find. The average number of microbes would be less than one cell per liter of water. “It would be like trying to find a needle in a haystack,” Affholder said.

Previous work by the same team showed that meteorites hitting Titan’s surface could melt the ice and allow some organics to reach the ocean. But this process is rare and doesn’t provide a steady or large supply of food.

NASA’s upcoming Dragonfly mission, set to launch in 2028 and reach Titan in 2034, will explore the moon in more detail. However, this new study suggests that while Titan remains an exciting place to search for life, we may need to lower our expectations. Titan’s organic-rich surface might not be as helpful for life as once believed.

Source: University of Arizona.