Electronic devices often struggle with stability because their electrical properties change with temperature.

But scientists at McGill University have made a surprising discovery about bismuth, a metal that could be used to create more stable and environmentally friendly electronics.

The research team found that ultra-thin bismuth shows a unique electrical effect that remains constant across a wide range of temperatures—from nearly absolute zero (-273°C) to room temperature.

This is unexpected, as most materials change their behavior with temperature.

“If we can understand and control this effect, it could lead to greener, more efficient electronics,” said Guillaume Gervais, a physics professor at McGill and co-author of the study.

A stable and sustainable future

The discovery could have major benefits for technology, especially for space exploration and medical devices, where stable electronic components are essential. Since bismuth is non-toxic and biocompatible, it is also a safer alternative to other materials used in electronics.

The researchers were shocked to find that the effect did not disappear at higher temperatures. “We expected it to vanish, but it just wouldn’t go away,” said Gervais. “I was so convinced that I even bet my students a bottle of wine that it would disappear—I was wrong!”

Inspired by a cheese grater

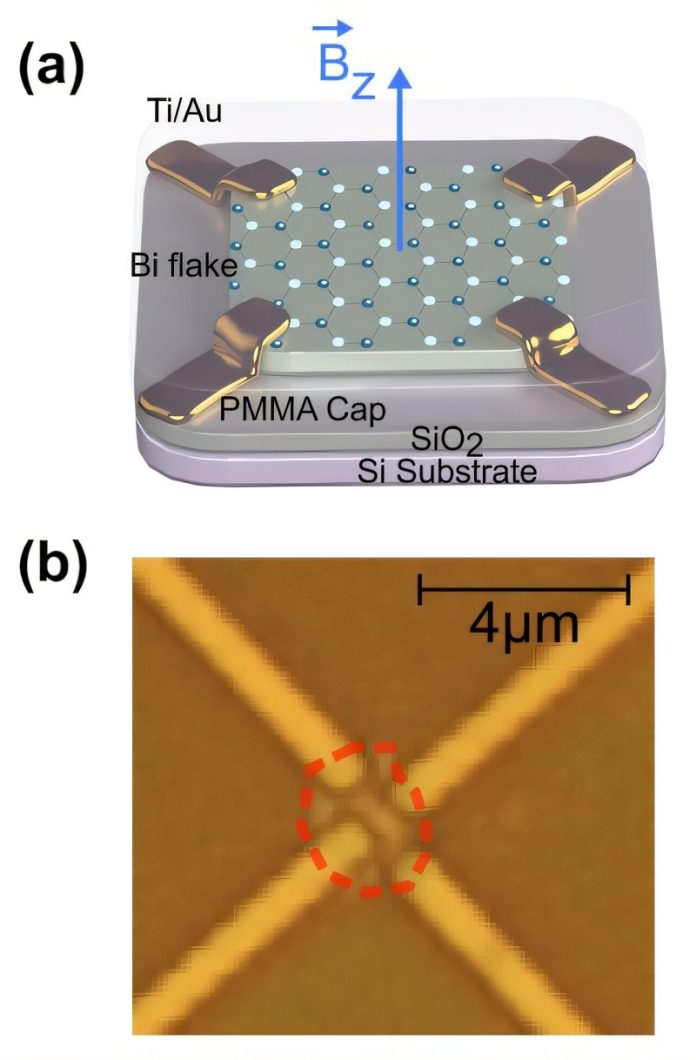

The study, published in Physical Review Letters, reports the discovery of a temperature-independent anomalous Hall effect (AHE) in a 68-nanometer-thick flake of bismuth. This effect, which creates a voltage perpendicular to an electric current, is usually found in magnetic materials. However, bismuth is diamagnetic, meaning it should not show this behavior.

To uncover this phenomenon, Ph.D. student Oulin Yu and colleagues developed a new way to create ultra-thin bismuth. Inspired by a cheese grater, they etched tiny trenches into a semiconductor wafer and then shaved off thin bismuth layers. These flakes were tested under extremely strong magnetic fields at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory in Florida.

A discovery that defies explanation

Scientists were puzzled because previous studies suggested that bismuth should not display AHE. “I can’t point to one theory that explains this fully,” admitted Gervais.

One idea is that bismuth’s atomic structure forces electrons to move in a way that mimics topological materials—exotic substances that could revolutionize computing.

The next step for the team is to investigate whether bismuth’s AHE can be transformed into the quantum anomalous Hall effect (QAHE). If successful, this could open doors to new electronic devices that work at higher temperatures than ever before.