A team of researchers, led by Cornell University, has found a way to make metals and alloys much stronger when they face extreme impacts.

By adding tiny “speed bumps” at the nanoscale level, they can prevent a common weakening effect that happens when metals are hit at high speeds.

This breakthrough could lead to tougher cars, planes, and armor that can better withstand crashes and extreme conditions.

The study, published on March 5 in Communications Materials, was led by Professor Mostafa Hassani from Cornell Engineering, in collaboration with researchers from the Army Research Laboratory (ARL).

The co-lead authors were Ph.D. student Qi Tang and postdoctoral researcher Jianxiong Li.

Why do metals fail under impact?

When a metal is hit at very high speed—like in a car crash or a bullet impact—it often becomes brittle and breaks instead of bending.

This happens because, under rapid force, the tiny defects inside the metal, called dislocations, move extremely fast.

Normally, these dislocations allow the metal to bend instead of breaking. But when they move too quickly, they start interacting with vibrations inside the metal’s atomic structure (called phonons), which slows them down and causes embrittlement.

To prevent this, the researchers created a new type of alloy made from copper and tantalum (Cu-3Ta).

The metal was designed with tiny grains and even smaller clusters of tantalum, which act as obstacles that prevent dislocations from moving too fast. By limiting how far these dislocations can travel, the metal remains flexible even when hit at extreme speeds.

High-Speed Testing

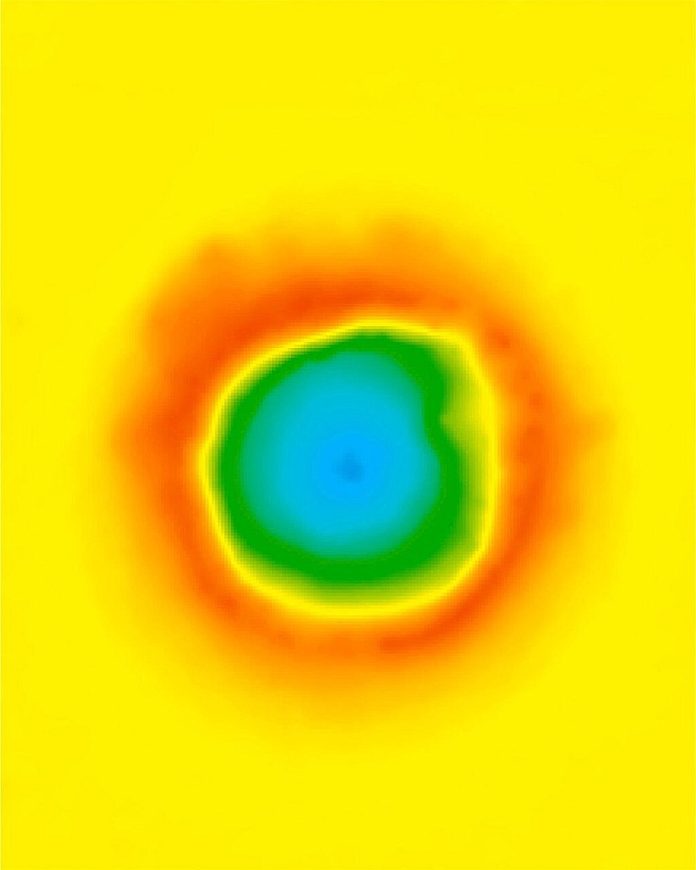

To test their new alloy, the researchers built a special setup where they launched tiny spherical particles at high speeds—up to 1 kilometer per second (faster than an airplane).

They compared how regular copper and the new copper-tantalum alloy reacted to these impacts. They also tested the materials at a slower speed by pushing a spherical tip into them to see how they deformed over time.

The biggest challenge was analyzing the data. The team developed a theoretical model to separate the effects of slow deformation from the effects of high-speed impact. Their results showed that in a normal metal, dislocations could move several dozen microns (millionths of a meter) before hitting a barrier.

But in the new alloy, dislocations could only move a few nanometers (a thousand times smaller), effectively stopping embrittlement.

This discovery is just the beginning. The researchers hope to further refine their approach by experimenting with different compositions and structures. If successful, this could lead to new generations of impact-resistant materials for transportation, defense, and industrial applications.

Co-authors of the study include Billy Hornbuckle, Anit Giri, and Kristopher Darling from ARL.

Source: Cornell University.