Scientists have discovered a new way for robots to move through rough terrain—without using a brain or a complex control system.

Instead, these “odd” robots rely on simple forces between their building blocks to propel themselves forward.

Researchers from the University of Amsterdam and the University of Chicago found that these unique robots can climb hills, cross sand, and navigate obstacles without any central control.

Their findings, published in Nature, could help improve robot movement in unpredictable environments.

How do these robots move?

Unlike traditional robots with computers and sensors, these odd robots are made of small motorized units connected by stretchy springs.

When powered on, the blocks push and pull against each other, creating movement without a central brain telling them what to do.

“The most surprising thing is how simple this is,” said researcher Colin Scheibner. “There’s no complicated programming—just basic physics guiding the motion.”

The secret to their movement lies in something called “odd elasticity.” In normal materials, when you push on them, they compress in the same direction. But in these odd robots, the force always stretches at an angle, creating a self-reinforcing motion.

As the robot moves, the terrain deforms it slightly. In response, its blocks adjust and push forward, continuing this cycle until it moves over the obstacle.

Tough, flexible, and self-sustaining

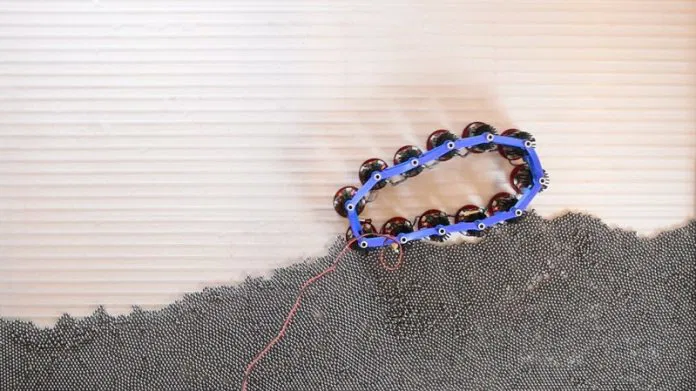

Despite their unusual movement, these robots are strong and reliable. Scientists tested them on challenging surfaces like sand and ball bearings, and they kept moving forward.

They also experimented with different designs:

- A worm-like chain that wiggles through tunnels and rough ground.

- A hexagonal “odd ball” that rolls smoothly on flat surfaces but crawls uphill when needed.

What’s even more surprising is how tough these robots are. Even when scientists turned off more than half of their individual units, they continued moving.

“It was shocking to see how robust they were despite their simplicity,” said Scheibner.

A new way to think about movement

These findings could have huge implications for robotics, materials science, and even biology. Scientists believe these robots could be used in situations where machines need to navigate rough terrain without direct human control, such as disaster zones or deep-sea exploration.

This research also raises fascinating questions about how movement evolved in early life forms that had no brain, like starfish and slime molds.

Scientists are now wondering: how small could these building blocks be? Could they shrink to the size of molecules and move on their own at microscopic levels?

This discovery may lead to new breakthroughs in robotics, chemistry, and beyond.

Source: University of Chicago.