Scientists are exploring a new way to deliver medicine in space using chitosan, a material made from shrimp shells.

Chitosan is already used on Earth to control how medicines are released in the body, and now researchers are testing if it works just as well in zero gravity.

Their early results suggest that astronauts can receive medicine safely and effectively in space.

A team from the University of Adelaide, in partnership with the German Aerospace Center (DLR), conducted the StarMed experiment by sending small vials of a drug mixture on a spaceflight. At the same time, they kept identical vials on Earth to compare the results after the spaceflight.

The researchers worked with nanoemulsions, tiny oil droplets (about 0.0001 mm in size) mixed into a water-based solution. These droplets carry the drug melatonin, which helps prevent bone loss—an issue astronauts face during long space missions.

To control how quickly melatonin is released, the scientists coated some of the oil droplets with chitosan, which acts as a protective barrier. Without this coating, the drug would be released too fast.

The experiment, led by Professor Volker Hessel at the University of Adelaide and Ph.D. student Modupe Adebowale, aimed to answer two key questions:

- How stable are these drug-carrying droplets in space?

- Does chitosan help control drug release in zero gravity?

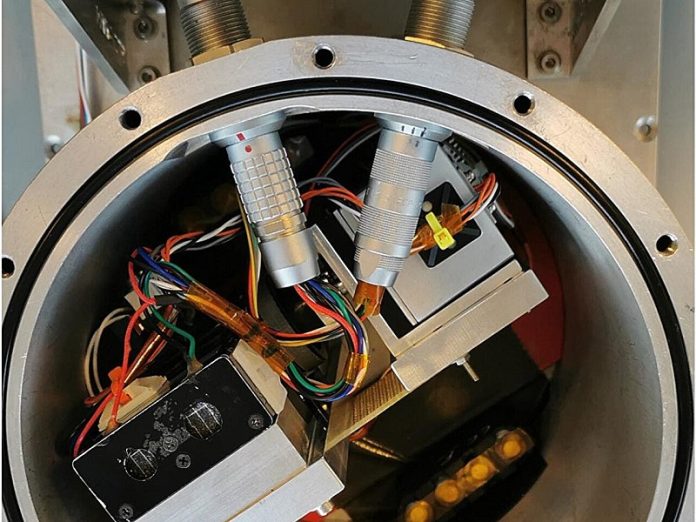

The team conducted the study with Dr. Jens Hauslage from DLR. Their nanoemulsions flew aboard a sounding rocket as part of DLR’s MAPHEUS 15 mission, launched in November 2024 from northern Sweden.

“This type of rocket provides a cost-effective way to test how things behave in space,” said Dr. Hauslage. “These experiments help us prepare for future human missions to the Moon and Mars by ensuring astronauts have the right medicine at the right time.”

Astronauts often take liquid medicines, which make up about 40% of the drugs used on the International Space Station (ISS). Having a reliable way to control drug release in space is important for their health.

The team’s first findings suggest that nanoemulsions without a chitosan coating became unstable in space, with the oil droplets growing larger and unevenly distributed. However, nanoemulsions with chitosan remained unchanged, which is good news for drug delivery.

“If confirmed, this means that chitosan-coated nanoemulsions are more stable in microgravity and can work well for medicine delivery in space,” said Professor Hessel. “It also shows that vibrations from the rocket launch didn’t affect their quality.”

This breakthrough could lead to better medicine for astronauts on long missions, ensuring they get the right dose at the right time.

Meanwhile, the University of Adelaide is also working on another space experiment called MiniWeed, which studies how altered gravity affects duckweed, a plant that could be used as a future food source for astronauts.