Scientists have long been fascinated by special magnetic materials where atoms arrange their spins in a spiral pattern.

These structures, called chiral helimagnets, could play a big role in next-generation electronics.

However, understanding and predicting how these spin spirals form has been a major challenge—until now.

A team from the University of California San Diego has developed a powerful new method to accurately model and predict these complex spin structures using quantum mechanics calculations.

Their study, published on February 19 in Advanced Functional Materials, could lead to better materials for advanced technology.

Cracking a 40-year-old mystery

“For more than 40 years, scientists have observed these helical spin structures in certain two-dimensional magnetic materials,” said Professor Kesong Yang, the senior author of the study. “But predicting them with accuracy has been extremely difficult.”

One major reason is that the spirals in these materials can stretch up to 48 nanometers (about 1,000 times smaller than a human hair). At this scale, it is incredibly hard to calculate all the interactions between electrons and atomic spins.

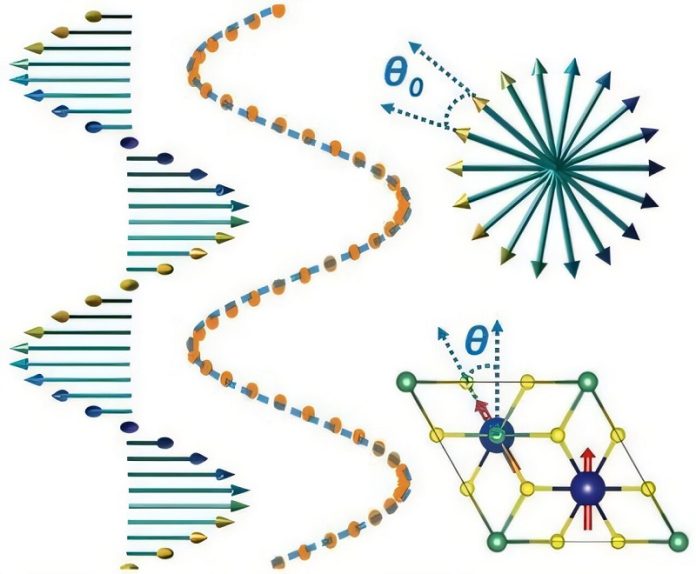

Instead of trying to model an entire system at once, the researchers took a different approach. They focused on how the energy of the system changes when atomic spins rotate between layers. By applying first-principles quantum mechanics calculations, they were able to map out the key features of these spirals.

“We designed a smart way to model the system using a small section of the material, called a supercell,” explained Yun Chen, the study’s first author and a Ph.D. student in nanoengineering. “This allowed us to get highly accurate results without needing an enormous amount of computing power.”

Predicting key properties of magnetic spirals

The team tested their approach on chiral helimagnets containing chromium, a metal well known for its magnetic properties. Using their model, they successfully predicted three important features:

- Helix wavevector – How tightly the spins twist in a spiral.

- Helix period – The length of one full spiral turn.

- Critical magnetic field – The strength of an external magnetic field needed to change the structure.

“This is an exciting breakthrough,” said Yang. “Now, we can precisely model and predict these complex spin patterns using quantum mechanics. This will help us design better materials for advanced electronics.”

By unlocking the secrets of these magnetic spirals, this research could lead to new energy-efficient technologies, from data storage to next-generation computing devices.

Source: UC San Diego.