A group of scientists from the University of California, Riverside, has found a new and exciting way to search for alien life—by looking for unusual gases in the atmospheres of distant planets.

Their work focuses on a group of gases called methyl halides, which are mostly made by bacteria, algae, fungi, and some plants here on Earth.

These gases are made up of a carbon and hydrogen group attached to a halogen like chlorine or bromine.

On Earth, they exist in small amounts, but on some alien worlds, they might build up in larger amounts—and that’s what makes them easier to detect.

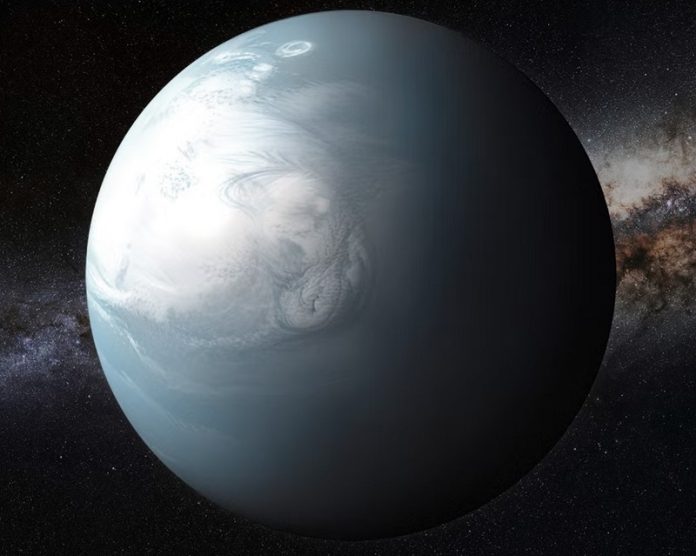

The scientists believe that Hycean planets—hot, ocean-covered planets with thick hydrogen atmospheres—are a good place to look for these gases.

These planets orbit small red stars and are too harsh for humans to live on, but they might be perfect for simple life forms like microbes.

Using the powerful James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), researchers could spot these gases in a planet’s atmosphere by studying how the planet’s light interacts with different chemicals.

Unlike Earth-like planets, which are harder to observe, Hycean planets are larger and give off clearer signals, making it easier to spot biosignatures like methyl halides.

Michaela Leung, the lead author of the study, said these gases are easier and faster to detect than others like oxygen or methane. In fact, JWST might find methyl halides in just 13 hours of observation, which would save both time and money.

Because Hycean planets are so different from Earth, gases like methyl halides might collect more easily in their atmospheres, making them more visible from far away.

If detected, these gases could suggest the presence of anaerobic microbes—tiny organisms that don’t need oxygen to survive.

This research adds to earlier studies that looked at other possible signs of life, like dimethyl sulfide, but methyl halides seem especially promising because they are easier to detect and may build up more in hydrogen-rich atmospheres.

In the future, even more advanced telescopes, like the planned European LIFE mission, could confirm the presence of these gases even faster—possibly in less than a day.

“If we find these gases on many planets,” Leung said, “it could mean that life is more common in the universe than we thought.”

For now, scientists will continue studying extreme environments on Earth, like the Salton Sea, to better understand what gases life might produce on other worlds.