A team of researchers at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology has developed a new 3D printing method that works faster and more efficiently than traditional techniques.

Inspired by the way trees grow, this process—called “growth printing”—allows for quick and cost-effective production of polymer parts without the need for expensive molds or equipment.

Their work was published in Advanced Materials.

A new way to print

Traditional manufacturing often involves injection molding, where molten plastic is shaped inside metal molds.

While effective for mass production, this process can be costly and complicated. 3D printing, which builds objects layer by layer, is more flexible but still slow and expensive.

The new “growth printing” method overcomes these issues. “We wanted to create a process that is faster, more affordable, and capable of making larger and stronger objects,” said Professor Sameh Tawfick, the project leader at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

The process begins with a liquid resin called dicyclopentadiene (DCPD), which is poured into a glass container placed in ice water.

When researchers heat a central point of the resin to 70°C, the reaction spreads outward at a speed of 1 millimeter per second. This is over 100 times faster than most home 3D printers and even 60 times faster than the fastest-growing species of bamboo!

As the heat spreads, the resin hardens into a solid material called poly-dicyclopentadiene (p-DCPD). This transformation is powered by a chemical reaction known as frontal ring-opening metathesis polymerization (FROMP). The reaction sustains itself with minimal energy, making it highly efficient.

To shape the printed object, researchers pull it out of the liquid resin—similar to dipping an apple in caramel.

By lifting, dipping, or rotating the solidifying material, they can control its form. For example, lifting and holding it still creates wavy patterns. This process mimics the way tree trunks grow outward, adjusting to environmental factors like wind and sunlight.

From nature to everyday objects

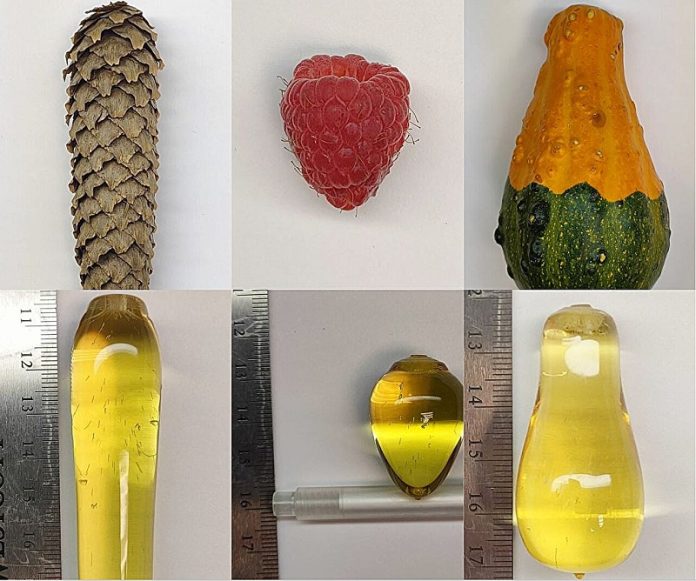

The team has used this method to create objects like a pinecone, a raspberry, and a squash. These objects are symmetrical around a central axis, making them easier to shape. More complex designs, like a kiwi bird with a small head and beak, are also possible. However, the process struggles with creating perfect cubes or complex curved shapes, much like nature itself.

Professor Tawfick hopes this simple and efficient technique can one day be used to manufacture large polymer-based products, such as wind turbine blades. “This method is inspired by nature, and its speed and efficiency make it highly practical for real-world applications,” he said.

With this breakthrough, 3D printing could soon become faster, more affordable, and more adaptable—just like the natural growth patterns that inspired it.