Some things just work better in pairs—like peanut butter and jelly, or famous duos like Simon and Garfunkel.

Now, scientists have discovered another unique partnership: semiconductors and bacteria.

A team of researchers at Cornell University has been exploring how tiny semiconductor particles called quantum dots can work with bacteria to turn sunlight into energy and create useful materials.

For the first time, they have figured out exactly how bacteria receive electrons from quantum dots.

They found that the electrons can travel through two different pathways: one direct route from the quantum dot to the bacteria, or an indirect path through special shuttle molecules.

These findings, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could help scientists design better biohybrid systems for clean energy and new materials.

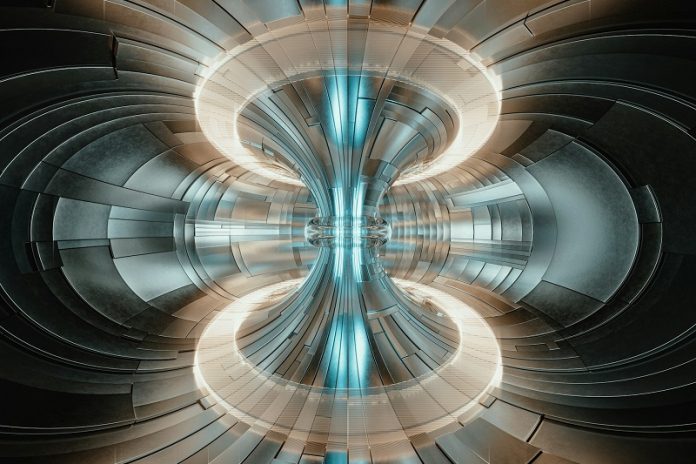

Quantum dots are tiny crystals that interact strongly with light.

They can absorb light and release energy in the form of electrons, which bacteria can use to carry out complex chemical reactions.

Researchers have suspected for a long time that there are different ways for electrons to move from quantum dots to bacteria, but no one had measured or imaged it precisely—until now.

“We discovered that there are different pathways for communicating,” said Tobias Hanrath, one of the study’s authors and a professor at Cornell Engineering. “This is a big step toward combining digital technology with microbial chemistry.”

The project started in 2019 and brought together experts in chemistry, biology, and engineering. Scientists Peng Chen, Buz Barstow, and Tobias Hanrath worked together to study these biohybrid systems at the single-cell level.

In 2023, they developed a special imaging platform to track where electrochemical activity was happening. For this latest study, they took a different approach: They wanted to see how electrons actually move from quantum dots to bacteria.

They teamed up with Warren Zipfel, an expert in optical microscopy, to use a special imaging technique that had never been applied to this problem before.

“The exciting moment was realizing that we could use this tool to probe interactions that had never been studied in this way before,” Hanrath said.

Using advanced imaging techniques, the researchers studied cadmium selenide quantum dots interacting with a type of bacteria called Shewanella oneidensis.

They found that the bacteria could receive electrons directly or indirectly through redox mediator molecules.

These two different pathways had different speeds and characteristics, which they measured using fluorescence lifetime imaging.

This discovery could lead to biohybrid systems that efficiently convert carbon dioxide into useful products like biofuels and bioplastics. It could also open the door to new ways of controlling microbes for industrial and environmental applications.

“If we can communicate with microbes, we could guide them to do things they wouldn’t normally do on their own,” Hanrath said. “This could have exciting possibilities for energy, materials, and even medicine.”