Scientists have long been puzzled by volcanoes that erupt far from the edges of tectonic plates—known as intraplate volcanoes.

These eruptions don’t follow the usual rules, since most volcanic activity happens along plate boundaries.

But a new study offers an exciting explanation: water stored deep inside the Earth may be the key.

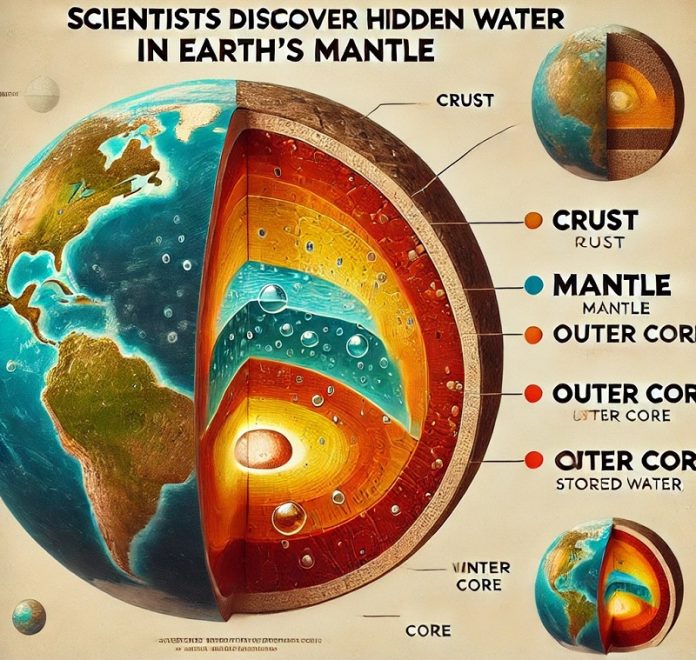

About 410 to 670 kilometers beneath our feet lies a layer called the mantle transition zone (MTZ).

Though we can’t see it, this zone may hold a huge amount of water—possibly as much as several oceans combined.

This water doesn’t flow like liquid oceans. Instead, it’s locked inside minerals like ringwoodite and wadsleyite, which form under high pressure.

How does the water get there? When tectonic plates sink into the Earth’s mantle—a process called subduction—they carry water-rich rocks deep underground.

Over millions of years, this can hydrate (or add water to) parts of the MTZ.

But scientists don’t yet know exactly where all this water is or how evenly it’s spread. Subducting plates vary in shape, size, speed, and location, which likely causes water to be distributed unevenly across the mantle.

To explore this, researcher Helene Wang and her team used models of how Earth’s plates have moved over the past 400 million years. They mapped where water-rich slabs might have traveled and released water into the MTZ. Then, they compared those areas to places where intraplate volcanoes have erupted over the past 250 million years.

Their results showed a strong link: around 42% to 68% of intraplate volcanoes happened above mantle areas that were more water-saturated. The connection was even stronger where the water had stayed in the mantle for 30 to 100 million years. This suggests that long-term water storage in the mantle may eventually lead to volcanic eruptions.

This discovery may help explain volcanic activity in places like eastern Asia, western North America, and eastern Australia—regions far from typical plate boundaries. On the other hand, areas like the Indian Ocean, southeast Africa, and the south Atlantic, which lie above dry parts of the MTZ, have seen little volcanic activity.

Overall, the study suggests that deep Earth water could play a surprising role in shaping our planet’s surface—even in places where we wouldn’t expect to see volcanoes.