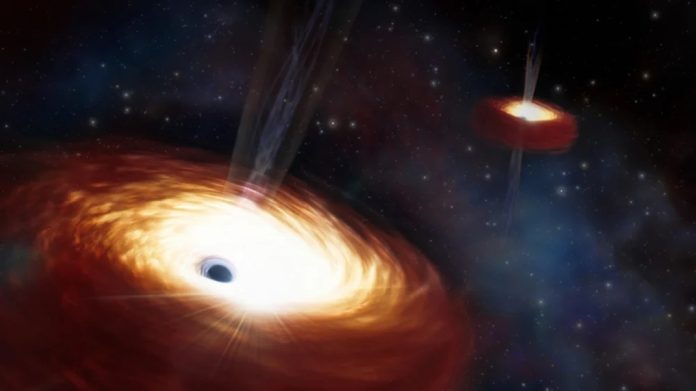

When it comes to safe places for life, supermassive black holes are probably the last place you’d consider safe for nearby planets, let alone life-bearing ones.

There are good reasons for this: those monsters at the hearts of galaxies suck down everything that comes into contact with them.

When they do that, they blast out killer radiation. Neither activity is necessarily good for life. Or is it?

As it turns out, radiation from these active galactic nuclei (AGN) can nurture life under the right circumstances.

Researchers at Dartmouth College and the University of Exeter simulated the effect of radiation from AGN on surrounding worlds.

Their work showed that strong UV emissions can either help transform a planet’s atmosphere or hinder any native life forms.

It’s somewhat like looking at what solar radiation has done for our own planet’s life forms. It all depends on how close the planet is to the AGN and if it already has life.

“Once life exists, and has oxygenated the atmosphere, the radiation becomes less devastating and possibly even a good thing,” says Kendall Sippy, the lead author of the study. “Once that bridge is crossed, the planet becomes more resilient to UV radiation and protected from potential extinction events.”

UV and Life

Ultraviolet radiation is strong stuff. It tears molecules apart, which can be bad news for life-associated compounds.

If the radiation is pervasive enough, it may keep any prebiotic compounds from forming at all, if the planet doesn’t have enough atmospheric protection.

Here on Earth, we have a protective ozone layer that filters some, but not all UV light from the Sun. It hasn’t always been that way.

In earlier times, the atmosphere didn’t filter as much of it out as it does today. What does get through can cause skin cancer through overexposure. It also “weathers” the skin, and causes premature aging.

Such radiation can affect our eyes, and, in enough concentration, can cause DNA damage. On the good side, UV helps humans produce vitamin D, and in the early epochs of Earth’s history, boosted the development of the complex molecules necessary to form the earliest forms of life.

High-energy light like UV reacts readily with oxygen in an atmosphere. The result is the buildup of ozone. A healthy ozone layer can help protect life from higher-energy radiation from space.

About two billion years ago, radiation from the Sun helped Earth’s earliest life forms oxygenate, and add ozone, to the atmosphere. As our planet’s protective ozone blanket thickened, it allowed life to flourish, producing more oxygen, and yet more ozone. This process enabled more complex life forms to evolve and spread around the planet.

“If life can quickly oxygenate a planet’s atmosphere, ozone can help regulate the atmosphere to favor the conditions life needs to grow,” said study co-author Jake Eager-Nash, of the University of Victoria. “Without a climate-regulating feedback mechanism, life may die out fast.”

Simulating the Effects of AGN Radiation

Since radiation from AGN can play a similar role for any nearby world, the research team wanted to simulate the effects of AGN radiation on Earth-like planets of varying atmospheric compositions.

If they already had oxygen in the atmosphere, the incoming ultraviolet light would set off the ozone-building chemical reactions. The more oxygenated the atmosphere, the greater the effect.

The team essentially recreated Earth’s atmosphere in the Archean period that began about 4 billion years ago and ended about 2 billion years ago. This is when much of our planet’s surface was under water and the atmosphere was considered “prebiotic” – that is, it was methane-rich and lacking in oxygen. The most complex forms of life at that time were the stromatolites – microbial mats.

Their computer simulation contained information about initial concentrations of oxygen and other atmospheric gases. Then they input levels of UV radiation to simulate that of an AGN.

“It models every chemical reaction that could take place,” said Sippy. “It returns plots of how much radiation is hitting the surface at different wavelengths, and the concentration of each gas in your model atmosphere, at different points in time.”

The result was a feedback loop for a planet that could handle the UV radiation and use it to create a thicker ozone layer which, in turn, protected the planet from the worst effects of the emissions.

The discovery was unexpected, partly because collaborators hadn’t worked on black hole radiation so they were unfamiliar with how much brighter an AGN could get than a star depending on how close a planet is to the AGN.

The increased radiation appears to have stimulated the atmospheric reactions and shows that high-energy emissions in UV are not necessarily the kiss of death for life on a planet near an AGN.

Written by Carolyn Collins Petersen/Universe Today.