After spending nearly 7,000 years buried deep in the mud of the Baltic Sea without light or oxygen, tiny algae have come back to life.

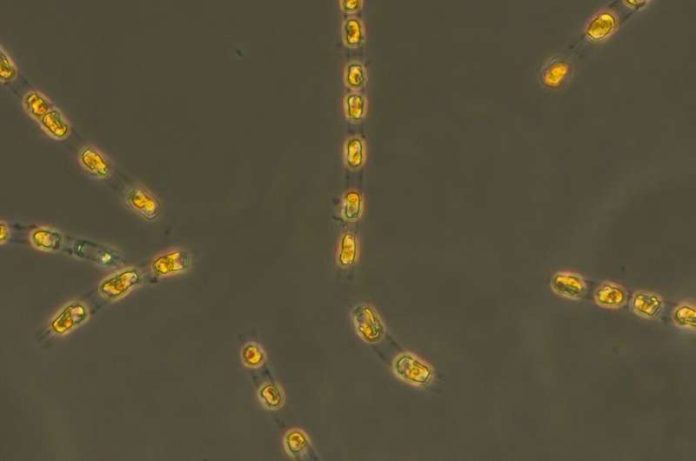

Scientists from the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde (IOW) led a fascinating study showing that ancient algae, specifically a type called Skeletonema marinoi, can survive in a dormant state for thousands of years and still grow and photosynthesize like their modern relatives.

The research was part of a larger project called PHYTOARK, which looks at how the Baltic Sea has changed over time by studying its past ecosystems.

The goal is to understand how current and future environmental changes might affect the sea.

Many living organisms, from bacteria to plants and animals, can enter a “sleep mode” called dormancy when conditions are not suitable for survival.

They slow down their metabolism and wait for better times.

This includes phytoplankton—tiny plant-like organisms in the water that photosynthesize. When conditions become harsh, these algae form tough, resting stages that sink to the bottom and can stay preserved in mud for centuries or even millennia, especially in areas without oxygen.

“These sediments are like time capsules,” says Sarah Bolius, the lead scientist of the study. They contain not just old cells but also clues about the environmental conditions at different times in history, such as salinity, temperature, and oxygen levels.

The researchers took mud samples from the seafloor, 240 meters deep, in an area known as the Eastern Gotland Deep.

These layers of sediment cover about 7,000 years of Baltic Sea history. From nine of these layers, scientists were able to “wake up” old algae by giving them nutrients and light. The revived algae grew, divided, and even performed photosynthesis—just like their modern counterparts.

Surprisingly, the oldest algae, which were about 6,871 years old, were still very healthy. They grew at a similar rate to modern algae, with an average of 0.31 cell divisions per day. They also produced oxygen through photosynthesis at similar levels, proving they were fully functional.

The team also studied the DNA of the revived algae using a method that compares short pieces of genetic material.

They found clear genetic differences between algae from different time periods, showing how the species evolved over the millennia. This also confirmed that the samples weren’t contaminated during the lab work.

This kind of study is called “resurrection ecology.” It involves bringing ancient life forms back to study how they’ve changed. The success of reviving such old algae is rare and marks one of the oldest cases of this kind from underwater sediments.

“These algae are among the oldest living organisms ever revived from dormancy,” says Bolius. The research opens up exciting possibilities.

Scientists can now grow ancient algae in the lab and study how they respond to different environmental conditions. This helps us understand how marine life adapted to climate and ecosystem changes over thousands of years.

Future studies will look deeper into the genes of these revived algae to learn more about how they’ve changed and what this means for the Baltic Sea’s past and future.