Last summer, astronomer Calvin Leung was excited to analyze data from a newly built radio telescope.

His goal was to pinpoint the exact location of fast radio bursts (FRBs)—sudden, intense flashes of radio waves from deep space.

These mysterious bursts come from far-off galaxies, and scientists are eager to learn where they come from and what causes them.

Leung, a researcher at UC Berkeley, had developed computer code to combine data from multiple telescopes, allowing his team to locate an FRB’s source with extreme accuracy.

But when his colleagues at the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME) aimed optical telescopes at the newly pinpointed burst, called FRB 20240209A, they were shocked by what they found.

A super-surprising location

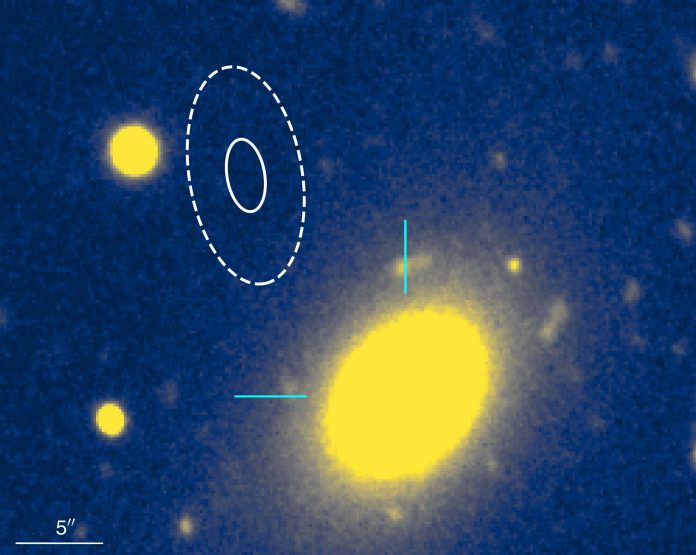

The FRB came from the outskirts of an old elliptical galaxy, about 2 billion light-years away. Scientists did not expect an FRB to come from this type of galaxy because it stopped forming new stars 11.3 billion years ago.

Most FRBs are thought to be caused by magnetars—highly magnetized, spinning neutron stars left over after a massive star explodes. But young, massive stars needed to create magnetars shouldn’t exist in such an ancient galaxy.

“This is not only the first FRB found outside a dead galaxy, but it’s also the farthest FRB ever detected from its galaxy,” said Vishwangi Shah, a PhD student at McGill University in Canada, who helped confirm its precise location. “It raises big questions about how such energetic events can happen in a place where no new stars have formed for billions of years.”

A step closer to solving the mystery

Since its discovery in February 2024, astronomers have detected 21 more bursts from the same source. This repeating FRB provides a great opportunity for scientists to study it further.

Shah and her colleagues think the FRB might come from a globular cluster, a dense region of very old stars that exists outside the galaxy itself. If true, this would be only the second FRB ever linked to a globular cluster. However, the other known example came from a young, active galaxy—not an ancient elliptical galaxy like this one.

“This challenges our current understanding of FRBs,” Shah explained. “We expected them to be tied to star-forming galaxies, but this discovery proves they can come from completely different environments.”

How CHIME is changing the game

Leung is one of the leading scientists working on CHIME, a massive radio telescope in British Columbia, Canada, that has already detected over 5,000 FRBs—more than 95% of all known bursts. But until recently, pinpointing the exact galaxies they came from was extremely difficult.

To improve accuracy, scientists have built three smaller telescopes, called outriggers, in different locations. The newest one just became operational in Hat Creek, California, joining two existing outriggers in British Columbia and West Virginia.

With these additional telescopes, CHIME can now determine the exact galaxy of an FRB 20 times more accurately than before. This means one new FRB per day can be traced back to its source, giving scientists a much better chance of figuring out what causes these bursts.

“With CHIME and its outriggers, we can do radio astronomy with unmatched precision,” Leung said. “Now, it’s up to optical telescopes like Hubble and James Webb to zoom in and find the source.”

This discovery proves that there’s still a lot to learn about FRBs. Scientists once thought they mainly came from young, star-forming galaxies, but this new FRB challenges that idea. If more bursts like FRB 20240209A are found, astronomers may have to rethink their theories about what causes these powerful cosmic flashes.

For now, CHIME and its growing network of telescopes will continue searching the sky, bringing us closer to solving one of astronomy’s biggest mysteries.