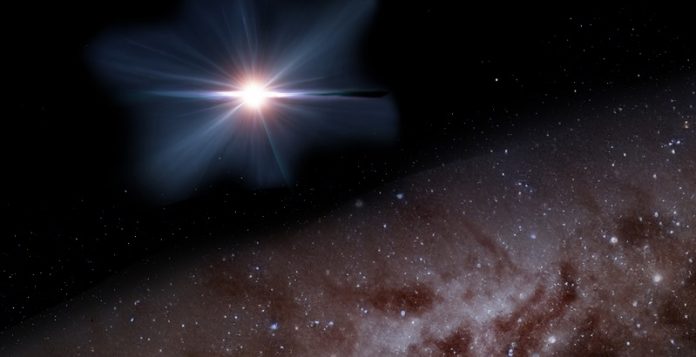

Scientists have discovered the oldest and most distant blazar ever seen, named J0410–0139.

This powerful object is located 12.9 billion light-years away and provides a rare glimpse into the universe when it was less than 800 million years old.

The discovery challenges what we thought we knew about black holes in the early universe—how big they could be, how fast they could grow, and how many existed back then.

A blazar is a type of active galactic nucleus (AGN), which is powered by a supermassive black hole at its center.

These black holes can be millions to billions of times bigger than the Sun. When they consume surrounding matter, they sometimes shoot out powerful jets of charged particles at nearly the speed of light.

A blazar is a special type of AGN where one of these jets is pointed directly at Earth, allowing scientists to study it in great detail.

The discovery of J0410–0139 was made possible by multiple observatories, including the U.S. National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Very Large Array, the NSF Very Long Baseline Array, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA).

Scientists were surprised to find such a massive and active black hole from this early period of the universe.

Joe Pesce, an NSF program director, explained, “This observation adds to growing evidence that supermassive black holes in the early universe aren’t behaving the way we expected.”

He added, “We don’t seem to understand their formation as well as we thought, but this is an exciting mystery to solve.”

The fact that scientists found this blazar suggests that there may have been far more AGNs—other galaxies with supermassive black holes—at that time than previously believed. Astronomer Silvia Belladitta noted, “Where there is one, there are likely a hundred more.” First author Eduardo Bañados compared it to seeing a cockroach in your home—if you spot one, there are probably many more hiding.

This discovery hints that supermassive black holes in the early universe may have grown faster or started out larger than scientists expected. It also raises new questions about how black holes formed and evolved in the early universe.

As researchers continue to study these distant objects, they hope to unlock more secrets about the universe’s origins and how it developed into what we see today.