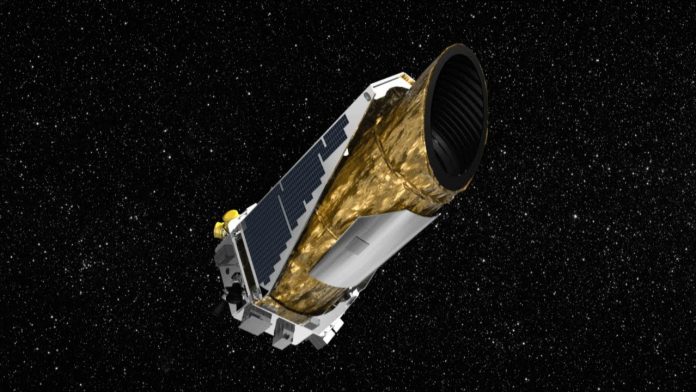

Kepler was one of the most successful exoplanet-hunting missions so far.

It discovered 2,600 confirmed exoplanets – almost half of the total – in its almost ten years of operation.

However, most data analysis focused only on one of the 150,000 targets it “intended” to look at. While it was making those observations, there were a myriad of background stars that also had their light captured incidentally.

John Bienias and Robert Szabó of Hungary’s Konkoly Observatory have spent a lot of time looking at those background stars and recently published a paper suggesting there might be seven more exoplanet candidates hiding in the data.

As with many space telescope missions, Kepler’s dataset is open to the public. NASA maintains a database with the raw data collected during the space telescope’s observations, and researchers are free to download it and analyze it as they see fit.

Plenty of interesting things are hiding in that data that were overlooked by the more than 3136 peer-reviewed scientific papers that have utilized Kepler’s data.

In the past, the authors have published other documents using the same datasets that described eclipsing binary stars and RR Lyrae stars, a type of pulsating variable star already existing in the data.

But while looking for more data on another paper about longer-period versions of those phenomena, they came across several stars whose light curve variability indicated something different – a planet passing in front of them.

These “transits”, as they are called, are one of the most common ways to identify exoplanet candidates, and have been used for decades, but this might be the first time they’ve been used on some of the 500,000 background stars in Kepler’s data.

That might be because the data is patchier, as the telescope was not focused on the stars in the background, making this resolution more difficult.

However, difficult does not mean impossible, and plenty of software solutions have been developed in the six years since the end of Kepler’s primary mission to help facilitate crunching large sets of data to look for planets around other stars.

One such system that has been around for a while is the Lomb-Scargle algorithm, developed in the 1970s and 80s and designed to detect periodic signals within time-series data.

This algorithm is a valuable step in finding both the eclipsing binaries the authors were initially looking for and the exoplanet candidates they recently described.

Other, more modern tools, proved more finicky, such as PSFmachine. This software package is designed to “deblend” light curves in Kepler’s data. Light curves are critical to exoplanet hunting as they show how the brightness of an object changes over time.

However, in Kepler’s background, multiple stars might be overlapping, causing a blending of their light curves. PSFmachine is designed to deal with that problem.

However, the authors described several issues in using the software, including its inability to create any stand-alone curves in one case. This seemed to be due to the placement of the stars compared to Kepler’s aperture (i.e., they were in the background) and the relatively small variations seen in the data.

Another tool developed near the end of Kepler’s mission was Pytransit, a Python-based software package that estimates the transmit models of light curves, including period, sizes, and orbital eccentricity. Candidate stars were also cross-referenced with the dataset from Gaia, which is designed to capture data about stars.

Utilizing all the tools, the authors identified seven exoplanet candidates. All were hot Jupiters, with sizes between .89 and 1.52 Jupiter’s radius and orbits between .04 and .07 AU. They also checked to see if any of those dips in light curves might have been caused by second planets orbiting the same star but came up empty-handed.

While seven additional candidate exoplanets might not seem like a lot compared to the 2,600 confirmed ones Kepler already found, combing over already released data shows how much more helpful context is sometimes publicly available if a researcher knows where and how to look.

As more powerful software packages and analytical tools are developed, there will undoubtedly be more discoveries coming out of older data sets like Kepler’s for some time to come.

Written by Andy Tomaswick/Universe Today.