Scientists have created a groundbreaking new material inspired by chainmail, and it could change the future of armor.

A research team led by Northwestern University has developed the first-ever two-dimensional (2D) mechanically interlocked material.

This unique material is incredibly strong and flexible, making it ideal for lightweight body armor, durable fabrics, and other high-performance applications.

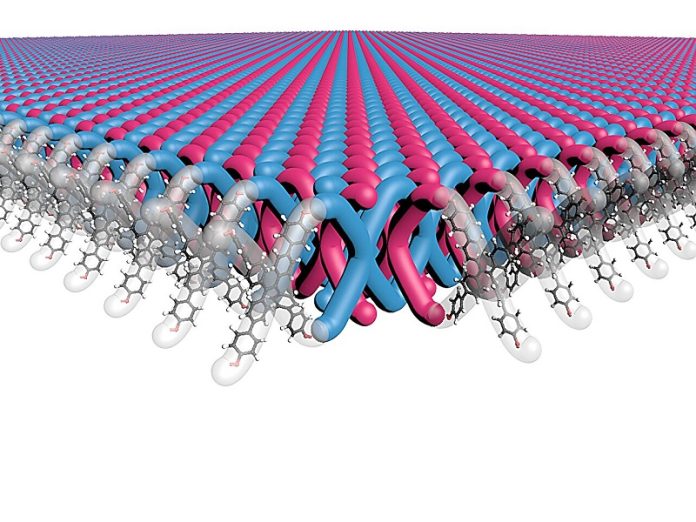

The material is made from interlocked molecules, similar to the links of chainmail. Unlike traditional materials that can tear in one spot, this design spreads force across the structure, making it much harder to break.

Published on January 17 in Science, the study showcases several firsts, including a record-breaking 100 trillion mechanical bonds per square centimeter in the material.

“We created an entirely new kind of polymer,” said Professor William Dichtel, who led the research.

“If you pull on it, the bonds can slide and distribute the force, making it very strong. Ripping it apart would require breaking it in countless places.”

For years, scientists struggled to make polymers with mechanical bonds. Dichtel’s team solved the problem by taking a fresh approach.

They started with X-shaped molecules, called monomers, and arranged them in a crystal structure. Then, they used a chemical reaction to link the molecules together, creating layers of interlocked polymer sheets.

Ph.D. student Madison Bardot came up with the innovative process. “It was a high-risk, high-reward idea,” said Dichtel. “We had to rethink what reactions were possible in these molecular crystals.”

The final material consists of many 2D layers, each made of interlocked monomers. Despite the rigid structure, the material remains surprisingly flexible. When dissolved in a liquid, the layers separate but don’t break apart, making them easy to manipulate for different uses.

To test the material’s potential, researchers at Duke University mixed a small amount—just 2.5%—of the new polymer into a strong fiber called Ultem, which is similar to Kevlar. The result was a composite material that was much stronger and tougher than Ultem alone.

Dichtel sees exciting possibilities for this new polymer in applications like lightweight armor and ballistic fabrics. “We still have more to study, but this material has exceptional properties in nearly every test we’ve done,” he said.

The study honors the late Sir Fraser Stoddart, a former Northwestern University chemist who first introduced the idea of mechanical bonds in the 1980s. His work on molecular machines earned him the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

“Molecules don’t naturally thread through each other, so Fraser developed clever ways to make interlocked structures,” said Dichtel, who once worked in Stoddart’s lab. “Our work builds on his ideas, but now we’ve made these bonds practical for large molecules like polymers.”

Dichtel’s team has already produced half a kilogram of the new polymer, a significant achievement compared to previous methods that only made tiny amounts. With scalable production now possible, the researchers are excited to explore the material’s potential.

This breakthrough not only paves the way for stronger, more flexible materials but also highlights how rethinking old challenges can lead to entirely new solutions. From body armor to advanced fabrics, this chainmail-like material could be the future of toughness and protection.