The South Pole-Aitken basin is the moon’s largest and oldest visible crater, formed around 4 billion years ago.

It’s like a giant time capsule, holding clues about the moon’s early history.

For years, scientists thought this massive crater was oval-shaped, created when an object hit the moon at a shallow angle, much like a skipping stone on water.

This theory suggested that not much debris from the impact reached the lunar South Pole, the area where NASA’s Artemis missions will soon land astronauts.

However, a new study led by the University of Maryland challenges this idea.

Published in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters, the research suggests the crater is more circular than previously thought, pointing to a more direct impact.

This discovery not only reshapes our understanding of the moon’s history but also has big implications for future lunar missions.

“It’s hard to study the South Pole-Aitken basin as a whole because it’s so enormous,” explained lead researcher Dr. Hannes Bernhardt, a geologist at the University of Maryland. “On top of that, 4 billion years of other impacts have changed its original look.

Our findings challenge old ideas about how this huge crater formed and spread materials across the moon.”

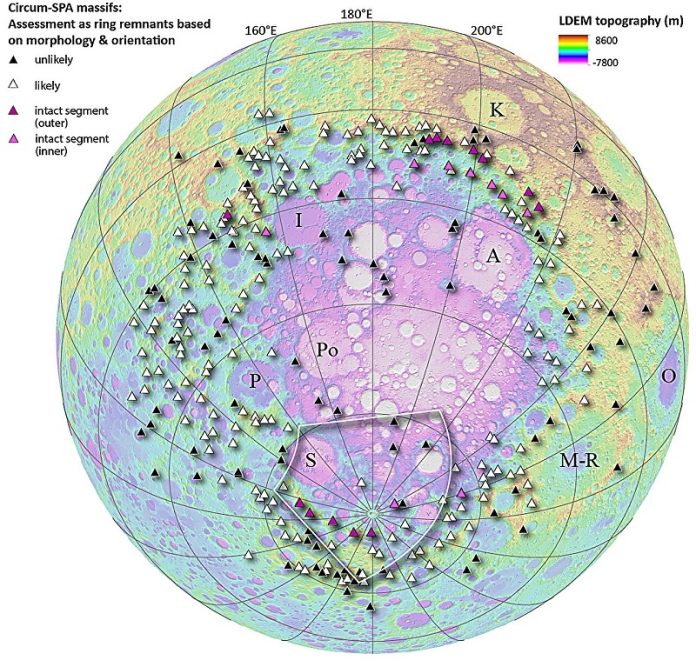

To investigate the basin’s shape, the team used high-resolution data from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

They identified and analyzed more than 200 mountain-like formations around the basin, which they believe are remnants of the original impact. These features revealed that the crater was likely rounder and formed from an object hitting the moon at a more vertical angle—similar to dropping a rock straight down.

This round shape means that the debris from the impact would have been spread more evenly around the crater, including the lunar South Pole.

According to Bernhardt, this is exciting news for Artemis astronauts and robots who will explore the region.

They may find rocks and materials from deep inside the moon’s crust and mantle, giving scientists a rare opportunity to study parts of the moon that are usually out of reach.

The discovery also supports recent findings by India’s Chandrayaan 3 rover, which detected minerals near the South Pole that seem to have come from the moon’s mantle. This evidence backs up the idea of a more vertical impact, which would have scattered such materials in that area.

These ancient rocks could hold important clues about the moon’s chemical makeup and help confirm theories about how the moon was formed. Many scientists believe the moon was created when a planet-sized object collided with Earth billions of years ago, throwing up debris that eventually formed the moon.

“This research provides key insights for future moon missions,” Bernhardt said. “It could help astronauts and mission planners know where to look and what kinds of materials they might find.”

The study suggests that the South Pole region is covered in a layer of material rich in rocks from the moon’s lower crust and upper mantle. These materials could reveal details about the moon’s formation and shed light on the major events that shaped our solar system.

“One of the most exciting parts of this research is how it could guide not just lunar missions but also future space exploration,” Bernhardt added. “Astronauts at the South Pole might find ancient materials that will help us better understand the moon’s origins and the history of our solar system.”