Astronomers at MIT have made a groundbreaking discovery, spotting the smallest asteroids ever detected in the main asteroid belt—a region between Mars and Jupiter filled with millions of space rocks.

These asteroids, some as small as 10 meters across (about the size of a bus), are tiny compared to the one that wiped out the dinosaurs, but they could still have a significant impact if they were to reach Earth.

The massive asteroid that caused the dinosaurs’ extinction was about 10 kilometers wide and struck Earth roughly 66 million years ago.

While such enormous impacts are rare, smaller asteroids measuring just tens of meters across are far more frequent.

These “decameter” asteroids could cause significant damage if they hit Earth, like the 1908 Tunguska event in Siberia or the 2013 Chelyabinsk explosion over Russia.

Until now, spotting such small asteroids in the main belt was nearly impossible. Scientists could only detect asteroids at least a kilometer wide.

But with a new approach, researchers have now identified more than 100 tiny asteroids, opening a window into their origins and potential paths toward Earth.

The study, published in Nature, was led by MIT scientist Artem Burdanov and included contributions from astronomers worldwide.

The team used a technique called “shift and stack” to analyze images of the main belt. This method involves combining multiple telescope images to reveal faint objects that would otherwise be lost in the noise.

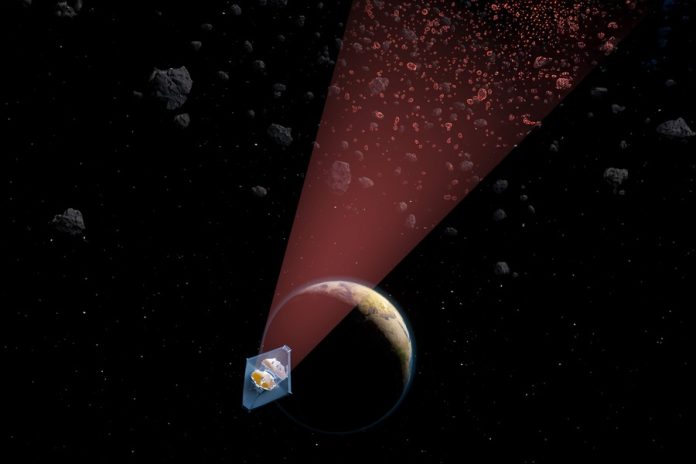

The researchers first tested their technique on data from ground-based telescopes, successfully spotting previously undetected asteroids. They then applied the method to infrared data from NASA’s powerful James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Infrared light is particularly useful for finding asteroids because it highlights the heat they emit, making even the smallest ones stand out.

Using JWST, the team analyzed over 10,000 images of the TRAPPIST-1 star system. Originally captured to study exoplanets, these images revealed much closer neighbors: 138 new asteroids in the main belt, ranging in size from a bus to several stadiums.

Finding these small asteroids is a big deal. According to the researchers, these space rocks often form from collisions between larger asteroids. Studying their sizes, shapes, and orbits helps scientists understand how asteroids evolve over time.

Some of these newly discovered asteroids may eventually leave the main belt and become near-Earth objects, which are closely monitored for potential collision risks. Detecting them early, while they’re still far from Earth, allows astronomers to track their orbits more precisely—a critical step for planetary defense.

“This is a totally new, unexplored space,” said Burdanov. “It shows what we can achieve when we look at data in new ways.”

The study also highlights the potential for modern telescopes and advanced data processing to uncover hidden populations of small objects in our solar system.

By studying these tiny asteroids, scientists can better understand the processes that shape the solar system—and help protect Earth from future impacts.