Solar cells, which turn sunlight into electricity, are becoming essential for powering homes, cars, and even small devices like watches.

But not all solar cells are created equal.

A newer type of solar cell made with a material called perovskite has shown promise because it’s cheaper and more eco-friendly to produce than traditional silicon-based solar cells.

However, one major problem has held them back: they fail too quickly, especially in humid conditions.

Dr. Tim Kelly, a chemistry professor at the University of Saskatchewan (USask), wanted to figure out why these perovskite solar cells don’t last.

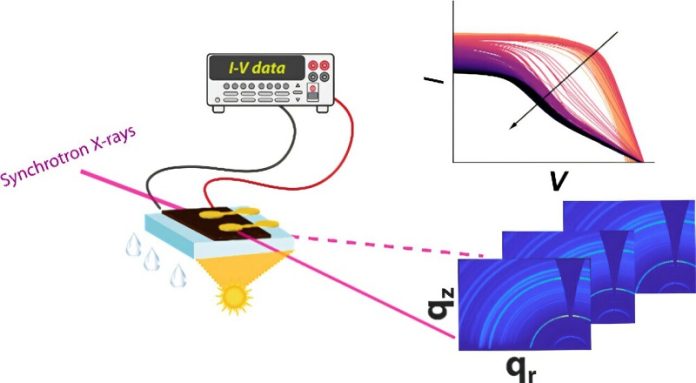

His team used advanced tools at the Canadian Light Source (CLS), a research facility, to watch the cells closely as they failed.

What they discovered not only explained the problem but also offered ideas for making these cells more reliable.

Kelly and his team thought humidity would directly damage the perovskite material itself since it absorbs moisture quickly.

However, their experiments showed something unexpected.

Using a powerful technique called X-ray diffraction, they found that humidity didn’t just affect the perovskite material—it caused ions (charged particles) in the material to move around.

These mobile ions migrated to the electrodes, which are the parts of the cell that carry electricity out. Once there, the ions corroded the electrodes, making the solar cell stop working.

“It turns out getting these things wet is not a good idea, just like most electronics,” Kelly explained.

While the problem is serious, Kelly’s research also pointed to ways to fix it. Possible solutions include:

- Using corrosion-resistant materials for the electrodes to prevent damage from the ions.

- Adding buffer layers that stop the ions from reaching the electrodes.

- Fully sealing the cells to keep out moisture entirely.

Each of these strategies could make perovskite solar cells more durable and practical for everyday use.

The research was made possible by the advanced tools at the CLS. These tools allowed the team to track changes in the cells in real time. In a regular lab, it might take 15–20 minutes to collect one data point during an experiment.

At the CLS, the same process takes just one to two seconds. This speed made it possible to see how the failure happened step by step.

“This material has a lot of potential,” Kelly said. Solving the moisture problem could make perovskite solar cells reliable enough for widespread use. For Kelly, the unexpected discovery was exciting: “It’s always thrilling when you learn something new or unexpected as a scientist.”

Thanks to this research, the dream of creating cheaper, greener, and longer-lasting solar cells is one step closer to reality.