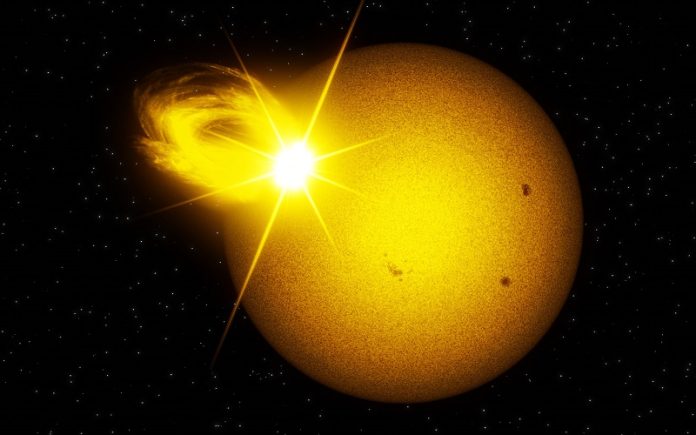

The sun, our temperamental star, is known for its powerful solar storms.

These storms can cause dazzling auroras and even disrupt technology on Earth.

But could the sun produce even more extreme outbursts?

A new study suggests it’s possible and that stars similar to our sun may release superflares—enormous bursts of energy—roughly once every century.

Superflares are incredibly powerful, releasing more than one octillion joules of energy in just a short time. That’s enough energy to potentially cause massive disruptions if one were to happen today.

To understand how often these events occur, scientists looked beyond the sun to study thousands of stars like it.

Their findings were published in the journal Science.

Direct measurements of solar activity only go back a few decades, so researchers rely on indirect methods to study the sun’s behavior over thousands of years.

Evidence of past solar outbursts can be found in ancient tree rings and glacial ice. However, these methods don’t provide a clear picture of how often superflares occur.

To get better data, a team of scientists turned to NASA’s Kepler space telescope, which observed the brightness of stars between 2009 and 2013.

By analyzing fluctuations in brightness, they could identify 2,889 superflares on 2,527 sun-like stars out of a dataset of 56,450 stars. This analysis provided evidence of 220,000 years of stellar activity.

The researchers carefully selected stars with temperatures and brightness similar to the sun and excluded other possible sources of bright flares, such as cosmic radiation or passing objects like asteroids. By focusing on “solar twins,” they determined that sun-like stars produce superflares about once every 100 years.

The team was surprised by how frequently these superflares occur. Earlier studies had suggested that superflares might only happen once every 1,000 to 10,000 years. However, those studies were less precise because they couldn’t always pinpoint the exact source of the flares.

“This shows that sun-like stars have a natural tendency to produce these extreme outbursts,” said Dr. Valeriy Vasilyev, the study’s lead author.

High-energy superflares originate from the intense magnetic activity of stars. This study provides the most sensitive and detailed evidence to date, helping scientists better understand the behavior of our own sun.

Scientists have also studied evidence of extreme solar events on Earth. For example, radioactive isotopes like carbon-14 in tree rings and ice cores reveal a history of powerful solar storms. Over the past 12,000 years, researchers have identified five major solar particle events, with an average occurrence of about once every 1,500 years.

One of the most intense events, known as the Carrington Event of 1859, caused telegraph systems to fail across Europe and North America. However, even this storm released only a fraction of the energy of a superflare.

The connection between superflares and extreme solar storms on Earth isn’t fully understood. “It’s unclear if superflares always come with coronal mass ejections or how they relate to particle events,” said Dr. Ilya Usoskin, a co-author of the study. This means historical records of solar storms might underestimate the frequency of superflares.

The study highlights the need for better space weather forecasting. Modern satellites and power grids are vulnerable to extreme solar activity. A superflare today could cause widespread damage to global infrastructure.

In 2031, the European Space Agency (ESA) will launch the Vigil space probe to improve solar storm forecasting. Vigil will monitor the sun from a unique vantage point in space, allowing scientists to detect dangerous activity earlier. Instruments for this mission are already under development.

“This research reminds us that extreme solar events are a natural part of the sun’s behavior,” said Dr. Natalie Krivova, one of the study’s authors. “Understanding them helps us prepare for the risks they pose.”

With this new insight into superflares, scientists are one step closer to predicting and protecting against the sun’s most extreme outbursts.