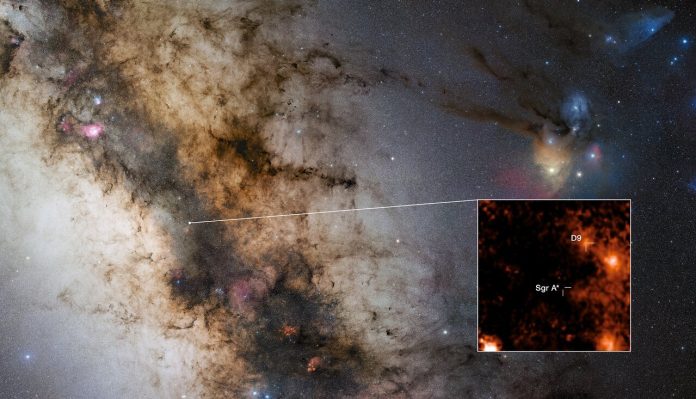

Scientists have made a groundbreaking discovery near Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy.

For the first time, researchers have found a pair of stars, known as a binary star, orbiting close to this powerful black hole.

This discovery sheds light on how stars can survive in extreme gravitational conditions and opens the door to finding planets near black holes in the future.

An international team of researchers used the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) to find the binary system, named D9.

The study, led by Florian Peißker from the University of Cologne, Germany, was published in Nature Communications.

Binary stars are common throughout the universe, but this is the first time one has been found near a supermassive black hole. The intense gravitational pull in this region usually destabilizes such systems. The discovery of D9 shows that binary stars can briefly survive even in such harsh conditions.

D9 is a young system, estimated to be only 2.7 million years old. However, the black hole’s gravity is so strong that it will likely cause the two stars to merge into one within the next million years. “This gives us a very short window to observe such a system,” explains co-author Emma Bordier, also from the University of Cologne.

For years, scientists believed that the area near a supermassive black hole was too extreme for new stars to form. However, the discovery of D9, along with other young stars near Sagittarius A*, disproves this idea. D9 also shows signs of gas and dust surrounding it, further suggesting it formed in this challenging environment.

D9 was found in the S cluster, a dense group of stars and objects near the black hole. Among these objects are mysterious “G objects” that behave like stars but appear as gas and dust clouds. While studying these, the team noticed unusual velocity patterns in D9, revealing it was actually two stars orbiting each other.

The discovery could also explain the nature of the G objects. Scientists think they might be binary stars that haven’t merged yet or remnants of merged stars.

This finding has broader implications. “Young stars often have planets forming around them,” says Peißker. “It seems likely that we’ll detect planets in the Galactic center soon.”

Future advancements, like ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope, will provide even sharper observations of this mysterious region, helping us uncover more secrets about the heart of our galaxy.