In the future, astronomers will study the atmospheres of planets as small as Earth and Venus orbiting other stars.

While Venus and Earth are often called “twins” because they are similar in size and density, their atmospheres are drastically different.

Venus is a hot, toxic world with an atmosphere made mostly of carbon dioxide, while Earth has a mild, nitrogen-rich atmosphere.

A new study from the Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences (IA) shows how scientists could tell these types of planets apart—even if they are light-years away.

The study used Venus as a model for exoplanets—planets outside our solar system.

By treating Venus as if it were in another star system, researchers tested whether techniques currently used to study large, hot exoplanets could work for smaller planets like Venus or Earth.

The results, published in the journal Atmosphere, show that these methods are effective and could be used with new telescopes in the coming decades.

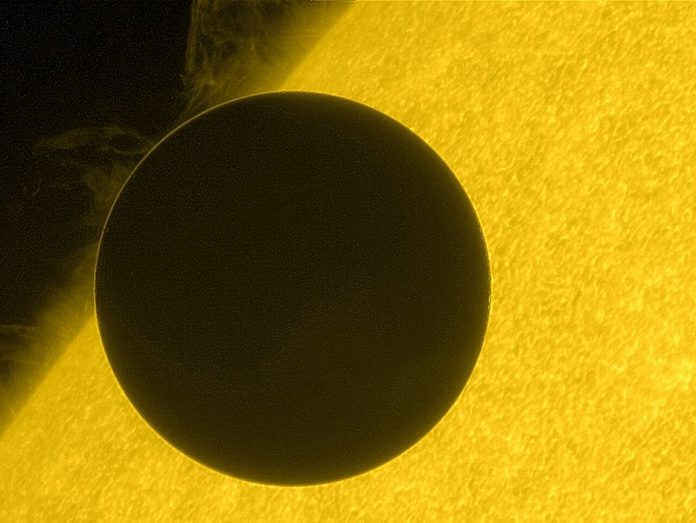

Venus crossed in front of the sun in June 2012, a rare event called a solar transit. This was the last Venus transit of the 21st century.

During such a transit, the atmosphere of the planet leaves faint traces in the sunlight as it travels toward Earth.

These traces contain clues about what the planet’s atmosphere is made of. This is the same technique scientists use to study the atmospheres of distant exoplanets when they pass in front of their stars.

The researchers analyzed data from the 2012 transit using techniques designed for studying exoplanets.

These methods work well for large, hot exoplanets, but it’s much harder to detect the atmospheres of smaller planets like Venus or Earth.

The team’s results show that it is possible to study smaller planets with current methods, especially when future instruments like the European Space Observatory’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) and the European Space Agency’s Ariel mission become operational in the 2030s.

Venus is an ideal test subject for studying exoplanets. Its thick atmosphere, which is about 90 times denser than Earth’s, creates a strong signal in the data.

Venus’s atmosphere is rich in carbon dioxide and undergoes a powerful greenhouse effect, making its surface hot enough to melt lead.

This extreme environment is much easier to detect than Earth’s more subtle atmosphere.

The study found faint signatures of carbon dioxide in the data from Venus. These signals wouldn’t appear in Earth-like atmospheres, showing how scientists could tell Venus-like planets apart from Earth-like ones.

However, the researchers note that more work is needed to confidently distinguish between the two.

Pedro Machado, one of the study’s authors, explained, “Venus’s dense and hot atmosphere makes it easier to detect chemical signals. It’s likely that the first Earth-sized exoplanet we study will have a Venus-like atmosphere.”

The study not only advances exoplanet research but also provides insights into planets in our own solar system.

By applying the same methods to Venus, the researchers detected small amounts of isotopes—variations of elements like carbon and oxygen. These isotopes can reveal how a planet’s atmosphere has changed over time, helping scientists understand its history.

The techniques tested on Venus could also be used for future studies of Jupiter, Saturn, and other planets when a bright star passes behind them. This will allow astronomers to analyze their atmospheres in new ways.

The European Space Agency’s upcoming mission to Venus, called EnVision, will focus on studying the planet’s evolution and past climate. This mission will build on the findings of the IA team, who have shown how studying Venus can inform our understanding of distant exoplanets.

Future telescopes like the ELT and space missions like Ariel will further expand this research. Ariel will study the atmospheres of about 1,000 known exoplanets, using the same techniques tested in this study.

Pedro Machado, a key member of the Ariel mission, emphasized the importance of linking the study of our solar system’s planets with those in other star systems.

By learning more about Venus and its extreme environment, scientists are paving the way to better understand the atmospheres of distant worlds—and perhaps even identify the first truly Earth-like planet.

Source: KSR.