In the movie Contact (1997), a scientist travels to the star Vega and finds herself surrounded by a cloud of debris, a scene that now seems uncannily accurate.

Recently, a team of astronomers from the University of Arizona took a detailed look at the real Vega system using NASA’s Hubble and James Webb space telescopes.

What they found was a surprisingly smooth and almost uniform disk of dust around the star, sparking new questions about planet formation in other star systems.

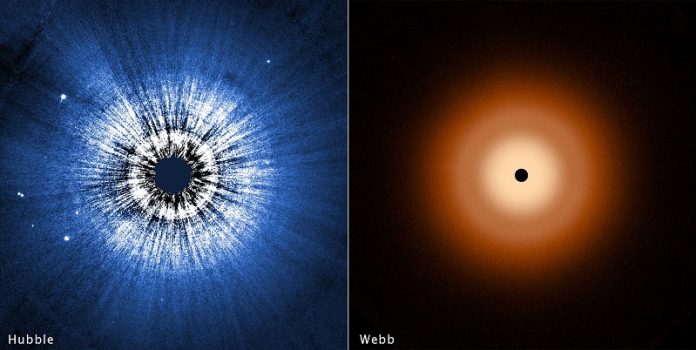

Using the Webb telescope’s infrared capabilities, scientists observed particles around Vega the size of sand, while Hubble captured even finer particles in the outer regions, similar to smoke.

The disk stretches nearly 100 billion miles in diameter, with the dust particles arranged in layers based on their size.

As starlight pushes smaller grains outward, different types of particles end up in different parts of the disk.

What’s surprising, however, is that Vega’s disk doesn’t show signs of large planets affecting the dust, as might be expected. In systems like our solar system, giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn shape the dust into rings or gaps.

Instead, Vega’s disk appears almost untouched, lacking the gaps or clumps that might suggest large planets are moving through it.

This has left researchers, like Kate Su, the lead scientist, puzzled, as they had expected to see something akin to “snow tractors”—planets carving paths through the dust.

Vega is one of the brightest stars in the night sky and has been known to have a disk of dust around it for decades. Since the 1980s, astronomers have found signs of warm dust around Vega, which hinted at leftover material from planet formation.

But with these new, detailed images from Hubble and Webb, scientists can see much more of Vega’s disk and understand how the dust is distributed.

Interestingly, Vega’s neighboring star, Fomalhaut, has a similar age and brightness but a much more complex disk with three distinct dust belts.

This raises the question: why did Fomalhaut seem to form planets, while Vega’s disk appears planet-free? According to team member George Rieke, this comparison between Vega and Fomalhaut could help scientists understand how planetary systems form in different environments.

These latest observations suggest that circumstellar disks like Vega’s may come in a wider variety than once thought, and understanding them may reveal new insights about the many ways planets could form—or not form—around stars.

With more research, scientists hope these clues will improve our understanding of the forces shaping distant planetary systems, even when planets themselves remain out of view.