For years, scientists have used the Milky Way as a model for understanding how galaxies form and evolve.

But new research suggests our galaxy may not be as typical as once thought.

Three recent studies, published in The Astrophysical Journal, reveal that the Milky Way’s structure and history differ in key ways from other galaxies of similar size.

“The Milky Way has been an incredible tool for studying galaxy formation and dark matter,” said Risa Wechsler, a professor of physics at Stanford University. “But it’s just one galaxy, and it may not represent the norm.

That’s why it’s important to study other galaxies like it.”

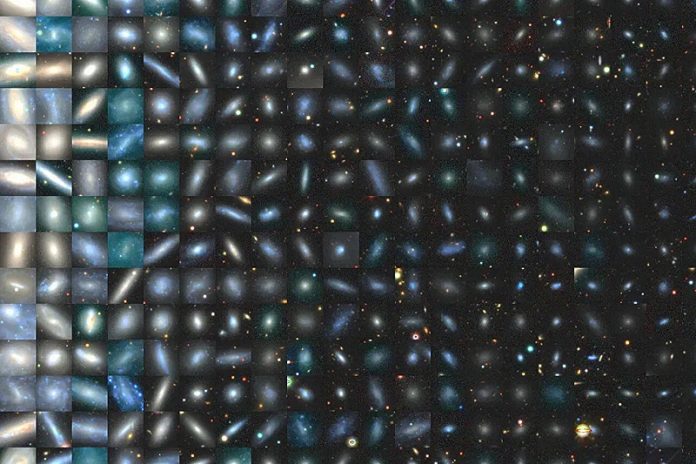

To explore this, Wechsler co-founded the SAGA Survey (Satellites Around Galactic Analogs), a project that compares galaxies similar in size to the Milky Way. Over the past decade, the SAGA team studied 101 Milky Way-like galaxies and their smaller satellite galaxies. The findings show that in many ways, the Milky Way stands apart.

One key discovery is that the Milky Way hosts fewer satellite galaxies than most of its counterparts. Satellites are small galaxies that orbit larger ones, like the Milky Way’s Large and Small Magellanic Clouds (LMC and SMC).

The study found that other galaxies similar to the Milky Way have anywhere from 0 to 13 satellites. While the Milky Way’s four satellites fit within this range, they are fewer than average.

Another study focused on star formation in satellite galaxies. Most galaxies like the Milky Way still have smaller satellites forming stars. However, in the Milky Way, star formation happens only in the massive LMC and SMC satellites. The smaller satellites have completely stopped making new stars.

“That’s a mystery,” said Wechsler. “Why have the Milky Way’s smaller satellites stopped forming stars? It could be due to a unique mix of older, inactive satellites and newer ones like the LMC and SMC, which only recently entered the Milky Way’s dark matter halo.”

The research also showed that satellite galaxies closer to their host are less likely to form stars, possibly because of the gravitational pull of the dark matter halo surrounding the host galaxy.

Dark matter is a mysterious substance that makes up 85% of the matter in the universe. It doesn’t interact with light or ordinary matter, but its gravity is strong enough to shape galaxies. Scientists believe galaxies form inside massive dark matter regions, called halos, which pull in gas and stars to create galaxies.

One goal of the SAGA Survey is to understand how dark matter halos affect galaxy evolution. By studying smaller halos and satellite galaxies, researchers hope to uncover the role dark matter plays on smaller scales.

“There’s probably dark matter running through you right now, and you wouldn’t even know it,” Wechsler explained. “It’s invisible, but it’s critical to how galaxies form and evolve.”

The third SAGA study compared real-world data with computer simulations. It found that current models of galaxy formation need to be updated to reflect the findings from the survey. Yunchong “Richie” Wang, a doctoral student at Stanford, led this part of the research.

“SAGA gives us a new way to study the universe by looking at satellite galaxies beyond the Milky Way,” Wechsler said. “Although we’ve mapped 101 galaxies, there’s still much more to learn.”

The results highlight the importance of studying multiple galaxies to understand the broader universe. While the Milky Way offers valuable insights, it’s clear that our galaxy is just one piece of a much larger cosmic puzzle.