Geologists studying the Cambrian rocks of the Grand Canyon have uncovered exciting new insights that challenge traditional views of Earth’s ancient history.

About 500 million years ago, during a period known as the Cambrian Explosion, a vast array of animal life emerged, marking a critical turning point in evolution.

Fossils from this time include many early animals with hard shells, the ancestors of today’s animals, including humans.

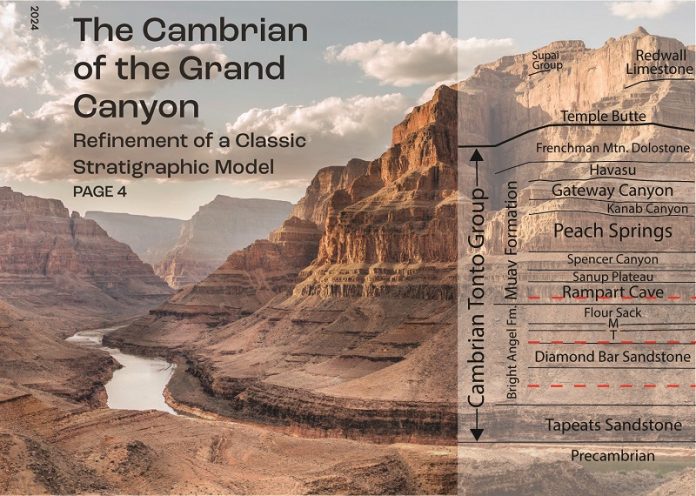

A recent study, led by Carol Dehler from Utah State University, along with Fred Sundberg from the University of New Mexico (UNM) and a collaborative team, re-examines the famous rock layers of the Grand Canyon’s Tonto Group.

This research, published in GSA Today, updates a well-known model for understanding the marine environments of the Cambrian period, first developed 50 years ago by geologist Eddy McKee.

McKee’s model suggested that the seas advanced gradually over the continents, creating slowly deepening layers of sediment.

However, the team’s new model offers a more detailed picture.

The researchers found evidence of both marine and non-marine environments and uncovered gaps where no sediment was deposited, suggesting a much faster pace of change and evolution than previously thought.

“Our findings show that the Tonto Group records a complex and varied history, with rapid shifts in environment and evolution,” says Karl Karlstrom, one of the UNM geologists involved.

This redefined model has important implications for geoscience education, offering students and researchers a deeper, more accurate understanding of how life on Earth evolved during this dynamic period.

According to co-author James Hagadorn from the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, “Our work in the Grand Canyon connects people to the science behind one of Earth’s most famous landscapes, reminding us that scientific knowledge is always evolving.”

Advanced dating techniques were crucial in this study. Using new U-Pb dating methods, the team was able to precisely date individual layers in the Tonto Group by analyzing zircon crystals within the sediment.

This process involved grinding the rock to extract these tiny sand-sized crystals, then determining their ages to narrow down the timeline of sediment deposition and fossil preservation.

With this technique, the researchers found that early marine animals, such as trilobites, evolved and went extinct in cycles lasting less than a million years.

The Grand Canyon’s Tonto Group offers a unique window into life 500 million years ago, revealing how rising sea levels and possibly intense tropical storms helped create environments that supported rapid growth in animal diversity.

This period saw extremely high sea levels, with much of Earth’s land covered in shallow seas, and no land plants yet present. In this ancient, hot world, conditions were ripe for new species to emerge and spread across the planet.

These discoveries not only provide a clearer picture of Earth’s past but also serve as a reminder of the ever-evolving nature of science.