A recent study suggests that Uranus’ small moon Miranda may have a hidden ocean beneath its icy surface, challenging what scientists once thought about this distant world.

If true, Miranda could join the ranks of other moons in our solar system that have environments capable of supporting life.

Tom Nordheim, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), and his team, including Caleb Strom from the University of North Dakota, used data from Voyager 2’s 1986 flyby and developed computer models to explore Miranda’s strange surface features.

Their findings, published in The Planetary Science Journal, point to the possibility of a vast ocean lying under Miranda’s icy crust.

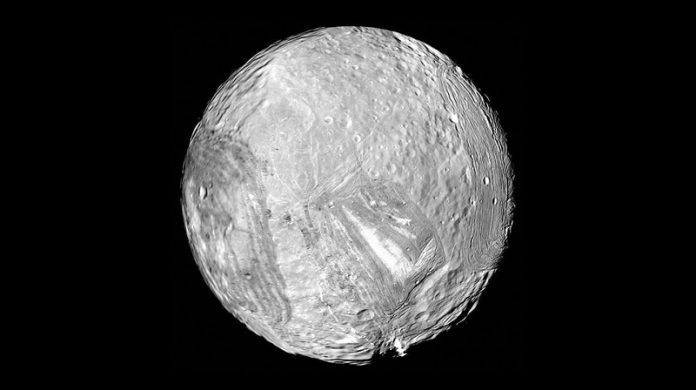

Voyager 2 captured images of Miranda’s southern hemisphere during its flyby.

The moon’s surface looks like a patchwork of ridges, cracks, and craters, which have puzzled scientists for decades. Researchers believe these unique features could be the result of tidal forces—gravitational pulls from Uranus and other nearby moons—causing heating and movement inside Miranda.

To investigate further, the team mapped out the cracks and ridges on Miranda’s surface and used computer simulations to understand the stress patterns that created these features.

Their models suggest that an ocean existed beneath Miranda’s surface between 100 and 500 million years ago, with the ocean stretching 62 miles (100 kilometers) deep under an icy layer about 19 miles (30 kilometers) thick.

For such a small moon—Miranda’s radius is only about 146 miles (235 kilometers)—this potential ocean would have taken up almost half of the moon’s body, an unexpected result for the researchers.

The team believes that tidal forces from Miranda’s neighboring moons may have played a key role in creating and maintaining this ocean.

When moons are in specific orbits, called resonances, their gravitational pulls can generate enough heat through friction to keep an ocean from freezing. A well-known example of this is Jupiter’s moon Europa, where tidal forces help sustain an ocean beneath its icy surface.

In the past, Miranda likely experienced a similar resonance with its nearby moons, causing enough heat to keep the interior warm and maintain a subsurface ocean. However, at some point, the resonance ended, and the heating slowed down, causing the moon’s insides to cool.

Despite this, the researchers believe that Miranda’s ocean may not have completely frozen yet. If it had, the surface would show specific cracks caused by expanding ice, but these cracks are absent.

This means that Miranda might still have a thin layer of liquid water beneath its surface today, which is remarkable considering the moon’s small size and distance from the Sun.

Miranda wasn’t expected to have an ocean because of its small size and old age. Scientists thought any heat leftover from its formation would have dissipated long ago, leaving it as a frozen ball of ice.

But as Nordheim pointed out, this wouldn’t be the first time predictions were wrong. Saturn’s moon Enceladus was also once thought to be frozen until NASA’s Cassini spacecraft discovered that it had a global ocean and active geysers.

Miranda may follow a similar path. If it does have an ocean, it could be an exciting target for future missions to study the potential for life beyond Earth.

However, as Nordheim cautions, there is still a lot we don’t know about Miranda and the other moons of Uranus. More data is needed before scientists can confirm the presence of an ocean.

For now, this new research opens up fascinating possibilities about the mysteries of Miranda and the other moons orbiting Uranus. Scientists are eager to learn more about these distant worlds and their potential to support life.

Source: Johns Hopkins University.