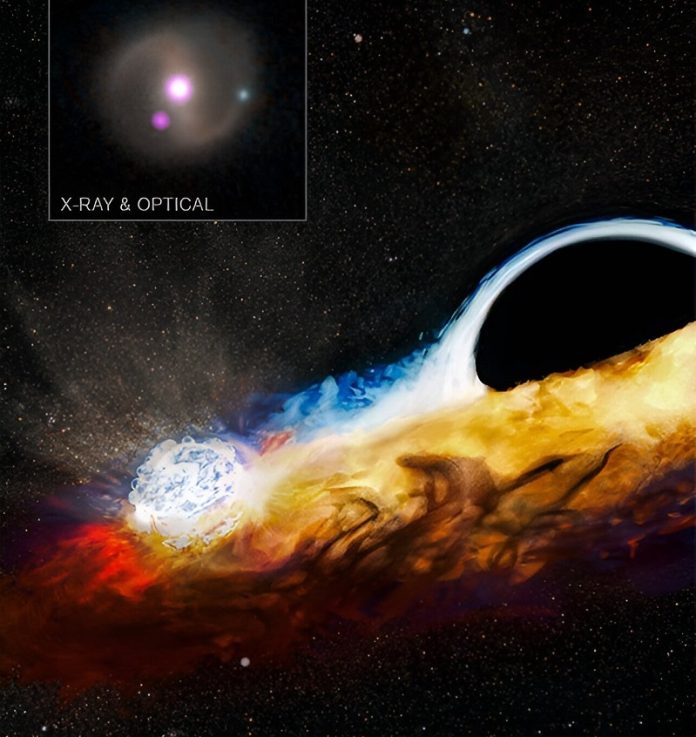

Astronomers have made a fascinating discovery: a supermassive black hole destroyed a star and is now using the debris from that star to smash into another object.

This discovery, made with NASA’s powerful space telescopes like Chandra and Hubble, has helped scientists connect two space mysteries that were once only vaguely linked.

The study was published in the journal Nature.

In 2019, astronomers observed a star getting too close to a black hole.

The black hole’s strong gravitational forces ripped the star apart, creating a disk of debris that swirled around it.

This leftover material forms a “graveyard” of sorts for the star, circling the black hole.

Over time, this debris disk expanded, and it eventually crossed paths with another object—possibly another star or a smaller black hole—that had been orbiting the supermassive black hole at a safe distance.

Now, this orbiting object crashes into the debris disk roughly every 48 hours, creating bursts of X-rays that NASA’s Chandra telescope captured.

To explain this, study leader Matt Nicholl from Queen’s University Belfast likened it to a diver jumping into a pool. Each time the diver hits the water, a splash is made. In this case, the object is like the diver, and the debris disk is the pool.

Every time the object hits the disk, it causes a massive “splash” of gas and X-rays, repeating this process as it circles the black hole.

This type of event, where a star is torn apart by a black hole, is called a “tidal disruption event.” Scientists have seen many of these, but they usually result in a single bright burst of light.

However, there’s another type of event, called “quasi-periodic eruptions,” where bright flashes of X-rays come from the center of galaxies.

These flashes happen repeatedly but had remained a mystery until now.

According to co-author Dheeraj Pasham from MIT, there has been much speculation that these two types of events were connected. With this discovery, scientists finally have proof that they are indeed linked. This means they have solved two cosmic mysteries in one go.

The event, now called AT2019qiz, was first observed in 2019 by a telescope in California.

By 2023, astronomers used Chandra and Hubble to study the debris left behind after the tidal disruption event. Further observations with other telescopes, including NICER and Swift, showed that the debris disk created bursts of X-rays about every 48 hours.

This discovery helps scientists understand why these eruptions happen after a star is destroyed and provides a new way to search for more of these events.

As they find more, astronomers will learn more about objects orbiting close to supermassive black holes, which could also become targets for future gravitational wave observatories.

Source: KSR.